China’s Crackdown on Same-Sex Love Stories Leaves Female Fans Heartbroken Over Lost Romances

For Cindy Zhong, a 30-something educator in China, unwinding once meant curling up with a romantic story about two men in love — tales that offered escape, fantasy, and emotional depth. But recently, her favorite writers and their stories have begun to vanish from the internet, victims of what many readers call China’s harshest crackdown yet on “Danmei” — a popular genre of same-sex romance fiction written mostly by and for women.

Danmei, known in English as “Boys’ Love,” features idealized male-male relationships that range from poetic and chaste to vividly erotic. While fantasy and historical settings are common, what draws millions of women readers is the emotional equality and mutual devotion often missing from portrayals of heterosexual relationships in traditional Chinese media.

“Women turn to Danmei for pure love, especially as they face pressure from families and society to marry and have children,” said Aiqing Wang, a senior lecturer at the University of Liverpool who studies Chinese internet culture.

A Literary Subculture Under Siege

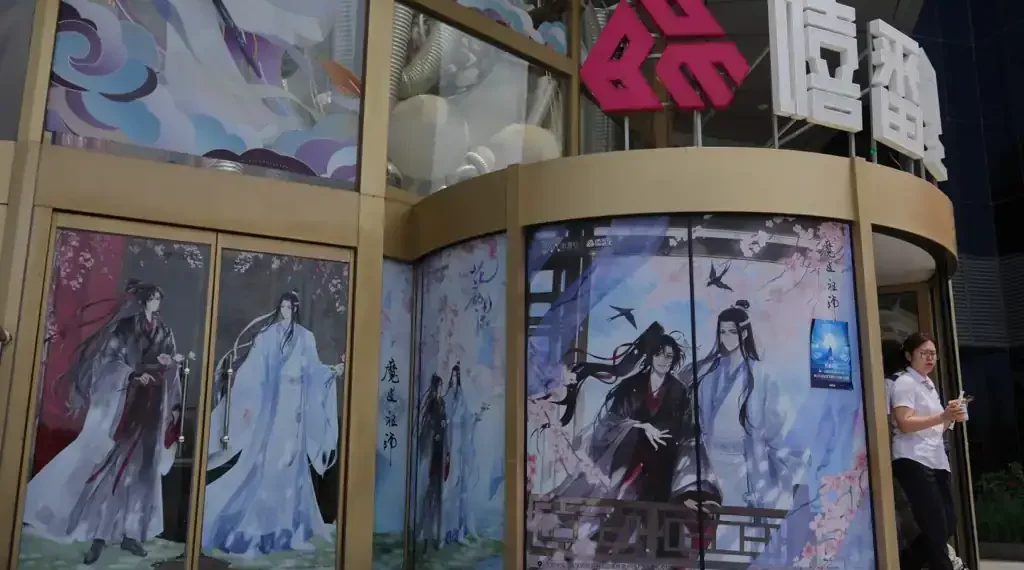

What began as a niche online community has exploded into one of China’s most vibrant storytelling movements. Once confined to digital fan fiction platforms, Danmei novels have been adapted into hit television dramas, video games, and internationally bestselling books, including Heaven Official’s Blessing and Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation — both translated into English and featured on The New York Times bestseller list.

But that visibility has also brought heightened government scrutiny. In the past year, at least dozens of Danmei writers have reportedly been interrogated, detained, or charged with “producing and selling obscene materials.” Some have deleted their online accounts, while others stopped writing altogether. Entire websites have gone offline or stripped their catalogs of anything remotely explicit.

“Chinese female readers can no longer find a safe, uncensored space to place our desires,” Zhong said.

From Flowery Prose to Silent Screens

Despite China’s official decriminalization of homosexuality in 1997 and its removal from the list of mental illnesses in 2001, LGBTQ+ representation remains tightly censored. While same-sex relationships aren’t illegal, public discussion of them — especially in art and entertainment — is heavily restricted.

Even so, Danmei became a cultural phenomenon, with its lush, metaphorical prose and dramatic emotional arcs captivating millions. Popular adaptations often sidestepped censorship by reframing the male leads as “close friends” or “brothers-in-arms,” while fans read between the lines.

“Danmei is a utopian existence,” said Chen Xingyu, a 32-year-old freelance teacher from Kunming. “I would be less happy without it.”

However, the author of two of the genre’s biggest hits, Mo Xiang Tong Xiu (real name Yuan Yimei), was sentenced in 2020 to three years in prison for “illegal business operations” related to self-publishing her novels. She was released on parole in 2021 — a warning, fans say, that creativity in this space comes with real risks.

Silencing the Authors

The true scale of the crackdown is hard to measure, but firsthand accounts are emerging online. Writers — mostly young women — have described being detained and questioned by police, especially in the northwestern city of Lanzhou. Some say they fear that a criminal record could destroy their futures.

Local police and provincial authorities have declined to comment, while attempts by foreign media to verify details have gone unanswered.

Even beyond mainland China, the ripple effects are spreading. Haitang, a popular Danmei platform headquartered in Taiwan, temporarily shut down in June, warning writers to comply with local laws “wherever they are located.” When it returned, thousands of stories were missing. Another international platform, Sosad.fun, with over 400,000 users, permanently closed in April.

A Vanishing World for Female Readers

What remains of Danmei online is a shadow of its former self — sanitized, abridged, and stripped of the eroticism that once defined it. For many readers, it’s like watching color drain from a vibrant world.

“Stories I read in high school were much more explicit than those I read nowadays,” said Chen. “I have to spend more time and try harder to find them. I need this content to fill my life.”

Some authors now publish overseas, circulating their stories through private online groups or imported paperbacks. Others have shifted to Japanese or Korean “Boys’ Love” comics, which are translated and shared quietly among Chinese readers.

Irreversible Change, Even in Silence

Experts believe the crackdown may succeed in erasing content, but not the cultural and emotional shift it represents.

“The awakening of female consciousness — the desire to read, to explore love, and to not be ashamed of it — is irreversible,” said Xi Tian, an associate professor of East Asian Studies at Bucknell University.

For readers like Zhong, Danmei was never just about escapism. It was a form of quiet rebellion — a way to imagine relationships built on mutual respect and emotional equality in a society where women’s desires are often muted.

As she put it simply, “When they silence our stories, they silence our freedom to dream.”

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.