The World’s First Twice-a-Year HIV Prevention Shot Could End Transmission — If People Can Actually Get It

A powerful new tool in the global fight against HIV has arrived — but whether it can live up to its promise may depend more on access than science.

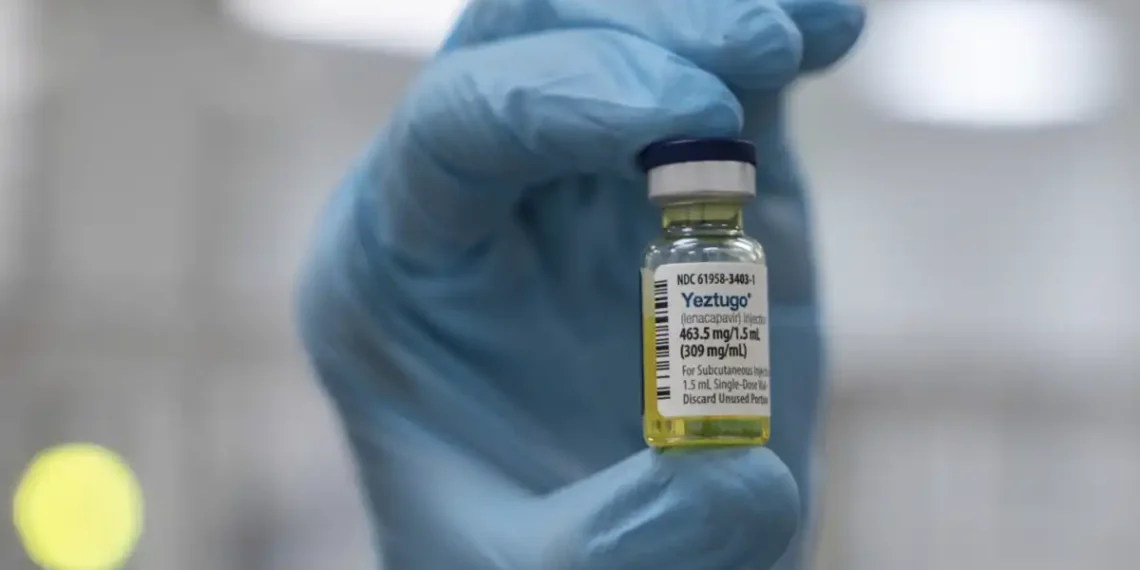

The U.S. has just approved the world’s only twice-yearly HIV prevention shot, a drug called lenacapavir, developed by Gilead Sciences. It’s being hailed as a potential game-changer: in two major studies, it nearly eliminated new HIV infections in people at high risk, outperforming existing daily pills.

“This really has the possibility of ending HIV transmission,” said Greg Millett, public policy director at amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research.

But despite the breakthrough, there’s a growing concern: will enough people actually get the shot?

How It Works: A New Kind of PrEP

While we still don’t have an HIV vaccine, PrEP — or pre-exposure prophylaxis — has become a frontline method of preventing infection. But current options, like daily pills or injections every two months, come with hurdles: people forget doses, miss appointments, or face stigma.

That’s where lenacapavir steps in.

Marketed under the new brand name Yeztugo (it’s already sold as Sunlenca for HIV treatment), the shot is given twice a year as two injections under the skin of the abdomen. The drug forms a slow-release “depot” that offers long-lasting protection.

Users must test negative for HIV before starting, and while the shot doesn’t prevent other STDs, its ease and effectiveness could dramatically expand prevention access — especially for people who can’t or won’t take a daily pill.

Game-Changing Results From Major Studies

The numbers speak for themselves:

- In a landmark trial of 5,300 young women and girls in South Africa and Uganda, zero participants who received lenacapavir became infected with HIV. By contrast, around 2% of those on daily PrEP pills did.

- A second study involving gay and gender-diverse participants in the U.S. and other high-risk countries found similarly high effectiveness.

For people like Ian Haddock of Houston, the difference has been life-changing.

“Now I forget that I’m on PrEP because I don’t have to carry around a pill bottle,” said Haddock, who took part in the study and now gets the shot every six months. “Just remembering a clinic visit every six months is a powerful tool.”

So What’s the Catch? Access and Affordability

Despite its promise, access to lenacapavir may be severely limited — especially in places that need it most.

- In the U.S., the shot will cost about $28,218 a year before insurance. Gilead says it expects private insurers to cover it and has financial assistance programs, but looming challenges remain:

- A Supreme Court case could overturn insurance coverage mandates for PrEP.

- Medicaid cuts under consideration in Congress could put it further out of reach.

- Much of the CDC’s HIV prevention outreach infrastructure was dismantled under the Trump administration, limiting efforts to get the shot to high-risk communities.

Carl Schmid of the HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute worries the opportunity is slipping away.

“We’re basically pulling the rug out of HIV prevention and testing and outreach programs.”

A Global Lifeline—But Not for Everyone

Worldwide, 1.3 million people are newly infected with HIV each year. Yet Gilead’s plan to expand lenacapavir access outside the U.S. is limited — and leaves out many middle-income countries.

- Gilead has partnered with six generic manufacturers to provide low-cost versions to 120 low-income countries, mostly in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean.

- Until those generics are available, Gilead will donate enough doses for 2 million people at no profit.

But that’s not enough, says Winnie Byanyima, executive director of UNAIDS.

“If it’s unaffordable,” she said, “it will change nothing.”

Countries in Latin America and elsewhere that don’t qualify as “low-income” could be stuck in limbo — unable to afford the brand-name version and ineligible for the generics.

Dr. Gordon Crofoot, a Houston physician who helped lead the U.S. trial, summed it up:

“Everyone in every country who’s at risk of HIV needs access to PrEP. We need easier access to PrEP that’s highly effective — like this is.”

The Bottom Line

Lenacapavir has the potential to become the most effective tool yet in the global fight to end HIV — offering protection that’s powerful, discreet, and refreshingly low-maintenance. But its success won’t just depend on science. It depends on the systems in place — or falling apart — to deliver it.

If access barriers aren’t addressed, this twice-a-year shot may join a long list of HIV breakthroughs that could save lives… if only people could get them.

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.