The Global Challenge of Iron Deficiency – Why Scientists Can’t Agree on Supplements

Iron deficiency is one of the world’s leading causes of disability, yet experts remain divided on when it becomes a serious issue and the best approach to treating it.

When Megan Ryan, a single mother from upstate New York, first experienced constant fatigue, she attributed it to the challenges of balancing full-time work and raising a three-year-old. She dismissed her exhaustion as just part of motherhood—until a routine medical check-up in June 2023 revealed that she had iron deficiency anemia.

Looking back, there were other warning signs: breathlessness during routine hikes and an unusual craving for ice—an indicator of pica, a common symptom of iron deficiency.

Ryan’s experience reflects a broader global health issue. Iron deficiency is the most common micronutrient deficiency worldwide, affecting one in three people. The condition is particularly prevalent among children and women of reproductive age, including pregnant women.

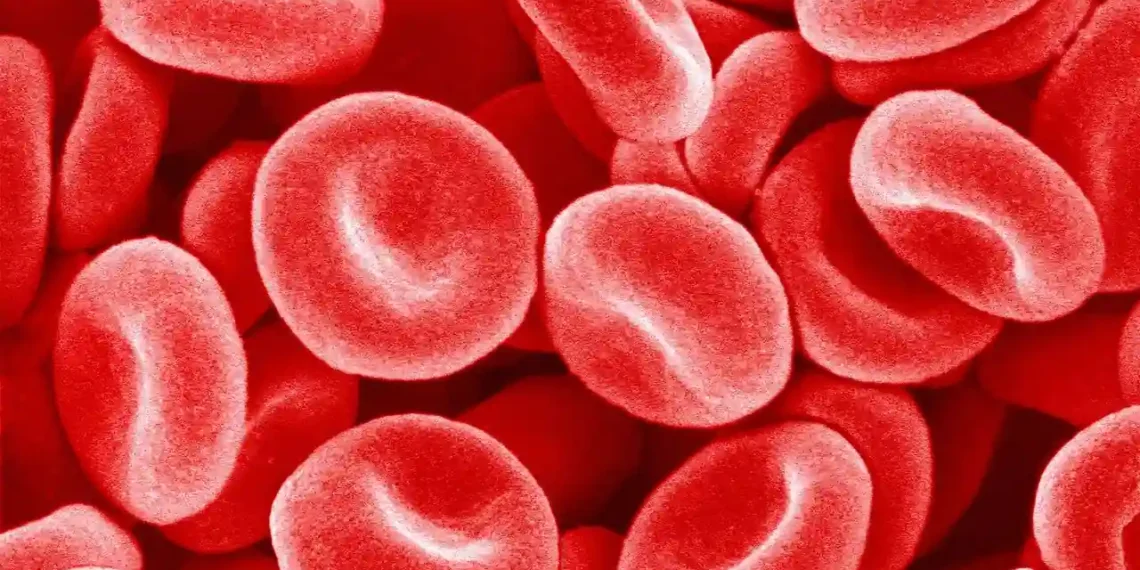

Iron is essential for red blood cell production and oxygen transport throughout the body. Without enough of it, various health problems can arise:

- Pregnant Women: Increased risk of premature birth, low birth weight, and impaired fetal brain development.

- Infants & Toddlers: Long-term developmental delays, behavioral issues, and reduced cognitive abilities.

- Adults: Fatigue, weakness, and in severe cases, life-threatening complications.

“It’s a major global problem,” says Michael Zimmermann, a professor of human nutrition at the University of Oxford. “It’s very common, it’s not going away fast, and it’s associated with significant disability.”

Some populations are more susceptible to iron deficiency than others:

- Women: Menstruation and pregnancy increase vulnerability. One study found that 46% of UK women had anemia at some point during pregnancy.

- Athletes: Endurance sports increase iron needs, putting athletes at higher risk.

- Vegetarians & Vegans: Plant-based diets often contain less bioavailable iron than meat-based diets.

- Frequent Blood Donors: Repeated donations can deplete iron levels.

- Individuals with Certain Medical Conditions: Kidney disease and celiac disease can reduce iron absorption.

Children are especially vulnerable due to rapid growth. “Infancy is the most rapid period of growth in our entire lifespan,” explains Mark Corkins of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “Without enough iron, the body struggles to produce the red blood cells necessary for proper oxygen delivery.”

Studies in Africa show that up to 70% of babies aged 6–12 months suffer from iron-deficiency anemia. Even in wealthier nations, the condition persists—affecting up to 4% of toddlers in the U.S.

Iron deficiency and anemia are not the same thing, though they are closely related.

- Iron Deficiency: Occurs when the body lacks adequate iron stores but may not yet impact red blood cell production.

- Iron-Deficiency Anemia: The stage where iron levels are so low that they affect hemoglobin levels, leading to fatigue, weakness, and other symptoms.

Diagnosis is typically made through blood tests measuring ferritin (a protein that stores iron) and hemoglobin levels.

The role of iron supplements is a topic of ongoing debate. While supplementation is often recommended for those with diagnosed deficiency, some researchers question its necessity for individuals without symptoms.

A review co-authored by clinical hematologist Sant-Rayn Pasricha found that while iron supplementation improved fatigue in women who reported feeling exhausted, it had no effect on women with iron deficiency who did not feel fatigued.

“For those who are clinically unwell with iron deficiency, treatment is beneficial,” says Pasricha. “But for those without symptoms, it’s unclear if supplementation improves health.”

This uncertainty is particularly relevant for children. One large study in Bangladesh found that iron supplements improved iron levels but did not enhance neurodevelopment. Another study revealed that infants who received high-iron formula performed worse on cognitive tests years later compared to those on low-iron formula.

Some experts argue that supplementing iron unnecessarily could have downsides, including digestive issues and altered gut microbiomes. Zimmermann warns that excessive iron supplementation in infants could encourage harmful bacterial growth, such as E. coli.

Given these risks, many experts advise consulting a doctor before starting iron supplements.

A balanced diet remains the best way to maintain adequate iron levels.

- Heme Iron (Easily Absorbed): Found in red meat, liver, poultry, and fish.

- Non-Heme Iron (Less Absorbed): Present in beans, lentils, nuts, and iron-fortified cereals.

- Vitamin C Boosts Absorption: Pairing iron-rich foods with sources of vitamin C (such as citrus fruits or bell peppers) enhances absorption.

In the U.S., the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that infants aged 6–12 months consume 11 mg of iron daily, while toddlers need 7 mg per day. Many pediatricians advocate for breastfed babies to receive iron drops starting at four months, as breastmilk alone does not provide sufficient iron. However, some researchers question this approach, citing potential drawbacks.

For those diagnosed with iron deficiency, recovery takes time. Megan Ryan, for instance, required iron infusions every two weeks for five months before her energy levels improved.

“It wasn’t a quick fix,” she says, “but I finally started feeling normal again.”

While iron deficiency remains a significant global challenge, ongoing research aims to clarify when and how supplementation should be used—ensuring that people receive the right treatment at the right time.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical advice. Always consult a healthcare professional regarding any concerns about your health or nutrition.

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.