Direct Stream Digital (DSD) audio, long considered a niche format among audiophiles, may more closely resemble true analog sound than conventional CD-quality audio, according to a Grammy-winning mastering engineer. The argument rests not on nostalgia or preference, but on how digital-to-analog converters already process most digital music before it reaches listeners’ ears.

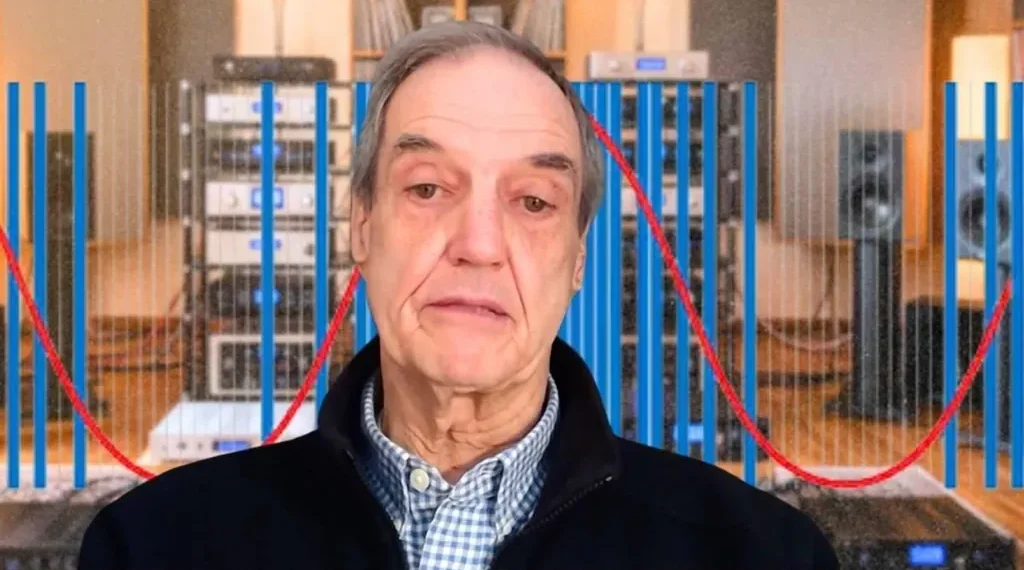

Tom Caulfield, a two-time Grammy Award winner and mastering engineer at high-resolution download platform NativeDSD, says the debate between DSD and Pulse Code Modulation (PCM) often overlooks a key technical reality. In most modern playback systems, including headphones, speakers, and hi-fi components, PCM audio is converted into a DSD-like signal internally before being rendered as analog sound.

That final conversion step, Caulfield argues, undercuts the idea that DSD is merely an exotic alternative.

“DSD is not a variation on PCM,” he said in an interview for NativeDSD. “It’s a completely different concept.”

PCM snapshots versus a continuous DSD stream

PCM underpins CDs, most downloads, and nearly all mainstream streaming services. The format works by taking discrete samples, or snapshots, of a sound wave at fixed intervals. For CD-quality audio, that means 44,100 samples per second.

DSD takes a fundamentally different approach. Instead of capturing individual snapshots, it represents sound as a continuous, high-speed stream of data that tracks changes in the signal moment by moment.

“DSD is a constant stream. It doesn’t stop,” Caulfield said. “So it doesn’t have those edges. It’s continuous.”

This distinction matters because analog sound itself is continuous. Sound waves in air do not arrive in frames or steps; they flow without interruption. PCM approximates this continuity by sampling frequently enough that the gaps are largely imperceptible to most listeners.

Caulfield maintains that approximation still imposes a structural limitation.

“Once PCM exists, everything after it is discontinuous,” he said. “From that point on, any processing is still dealing with samples.”

Why higher-resolution PCM does not fully solve the problem

To explain the difference, Caulfield often compares PCM audio to film projection.

“Each frame is a still image,” he said. “It doesn’t move at all. The illusion of motion comes from how many frames pass per second. PCM is like that.”

Higher-resolution PCM formats, such as 96kHz or 192kHz audio, increase the number of samples captured per second, improving fidelity and reducing audible artifacts. However, Caulfield argues they remain bound by the same underlying model.

“You can increase resolution or frame rate,” he said, “but you can’t recover something that was never captured.”

DSD, by contrast, operates more like a radio carrier signal. It modulates information continuously at an extremely high rate—2.8 MHz in its base form, known as DSD64, or 64 times the sampling rate of CD audio.

If the audio content were stripped away, Caulfield explains, what would remain is a form of broadband noise rather than a series of identifiable steps. That lack of hard edges is central to why DSD behaves differently when converted back into analog sound.

What listeners say they hear

Among audiophiles who compare the two formats, descriptions tend to converge around similar themes. Discussions on specialist forums frequently cite a greater sense of space, presence, or realism when listening to native DSD recordings.

On the Steve Hoffman Music Forum, some listeners describe ambience and reverb tails as lingering longer in DSD playback, giving recordings a more natural decay. Others point to a feeling of depth or “air” that they find harder to perceive in PCM versions of the same material.

Professional reviewers have echoed those impressions. Writing in Positive Feedback, Rushton Paul described DSD playback as having a level of transparency he does not associate with PCM, saying high-rate DSD files sounded “closer to the music and the artists,” with less apparent processing in the signal path.

Not all listeners agree. On forums hosted by manufacturers such as PS Audio, some users describe DSD as smoother or more relaxed, sometimes at the expense of perceived punch or immediacy. Others prefer PCM for what they hear as greater dynamic contrast and energy.

Caulfield does not dispute those differing reactions. Instead, he links them to the technical demands of reconstructing PCM audio during playback.

Filters, artifacts, and reconstruction

To turn PCM samples back into a continuous analog waveform, digital-to-analog converters rely on reconstruction filters. These filters smooth the stepped signal, but they can also introduce subtle side effects.

Engineers commonly point to issues such as phase shifts, pre-ringing, or small ripples in frequency response. While often measurable at levels well below audibility, Caulfield argues they can still influence how sound is perceived.

DSD’s very high sampling rate shifts much of that filtering burden far above the audible range. Any artifacts produced by the process are pushed into ultrasonic frequencies, reducing their potential impact on what listeners hear.

“The object,” Caulfield said, “is to get around the discontinuous nature of PCM.”

A niche format with broader implications

Despite these arguments, DSD remains a minority format. File sizes are large, editing is more complex, and native DSD recordings require specialized workflows. Many releases labeled as DSD originate from PCM masters, limiting the format’s theoretical advantages.

Still, Caulfield believes understanding how DSD works helps explain why some listeners consistently prefer it, particularly when recordings are captured and mastered entirely in the format.

Whether those differences matter, he acknowledges, depends on individual hearing, playback equipment, and musical priorities. For some, the convenience and flexibility of PCM outweigh any perceived sonic trade-offs.

For others, the appeal lies in reducing the number of conversions between recording and playback.

“You can’t create reality because reality doesn’t exist,” Caulfield said. “All you can create is more frames.”

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.