A water-soluble plastic casing designed to dissolve at the end of a product’s life is being developed as a potential response to the world’s rapidly growing e-waste problem. The material, known as Aquafade, could make it easier to recover valuable electronic components while reducing the amount of discarded plastic sent to landfill or incineration.

The concept arrives as governments and manufacturers face mounting pressure to address the environmental and economic costs of electronic waste, which continues to rise far faster than global recycling capacity.

A growing global waste challenge

The scale of the problem is stark. A United Nations report published in 2024 estimated that 62 million tonnes of electronic waste were generated worldwide in 2022. Most of it was dumped or burned rather than recycled, raising concerns about soil contamination, water pollution, and human exposure to toxic substances such as lead and mercury.

Beyond environmental risks, the UN report highlighted a major economic loss. Around $62 billion worth of recoverable materials, including rare earth elements critical to modern electronics, were discarded. Despite their importance to industries ranging from consumer electronics to renewable energy, only about 1% of global demand for rare earths is currently met through recycling.

With e-waste volumes increasing five times faster than formal recycling rates, researchers and startups are searching for ways to remove bottlenecks that make recycling costly, complex, and labor-intensive.

Water-soluble electronics casing and the promise of easier recycling

Aquafade is one such attempt. Developed by a small team of designers and scientists in the United Kingdom, the plastic is fully water-soluble and can dissolve completely within roughly six hours when submerged. The idea is to use it as an outer casing for electronic products such as keyboards or small devices.

Once a product reaches the end of its useful life, the casing could be dissolved at home, leaving behind the internal electronic components. Those parts can then be more easily separated for recycling or recovery, reducing the need for manual disassembly, which is often cited as one of the most expensive stages of e-waste processing.

“For most electronic products, when they’re being recycled, it’s the disassembly that’s the real hassle, and really labor-intensive,” said Samuel Wangsaputra, one of Aquafade’s inventors. He said the material could allow part of that process to happen outside centralized recycling facilities, potentially lowering costs and emissions linked to transport.

Inspiration from everyday products

The idea for Aquafade did not originate in a laboratory. Wangsaputra traces it back to a moment of curiosity while washing dishes and noticing the thin, transparent film used in dishwasher detergent pods. That film dissolves in water without leaving visible residue.

Wondering how it worked, Wangsaputra began experimenting and later teamed up with co-inventor Joon Sang Lee. The pair had already founded Pentaform, a UK-based startup focused on affordable and accessible computing, in 2019.

To explore the concept further, they collaborated with materials scientists Enrico Manfredi-Haylock and Meryem Lamari at Imperial College London. Their research led them to polyvinyl alcohol, or PVOH, a polymer already used in products such as laundry and dishwasher pods.

According to Wangsaputra, the material met key requirements. It is water-soluble, considered safe for consumer use, and capable of breaking down further in sewage systems under controlled conditions.

Balancing solubility and durability

One of the central technical challenges was reconciling two opposing needs: the casing must survive everyday use, including exposure to moisture, but dissolve reliably at the end of its life.

The team addressed this by developing a thin waterproof coating, also made from a plastic polymer, applied only to the outer shell. In its finished form, the casing is designed to withstand immersion in water up to five meters deep for around 30 minutes, covering scenarios such as spills or rain.

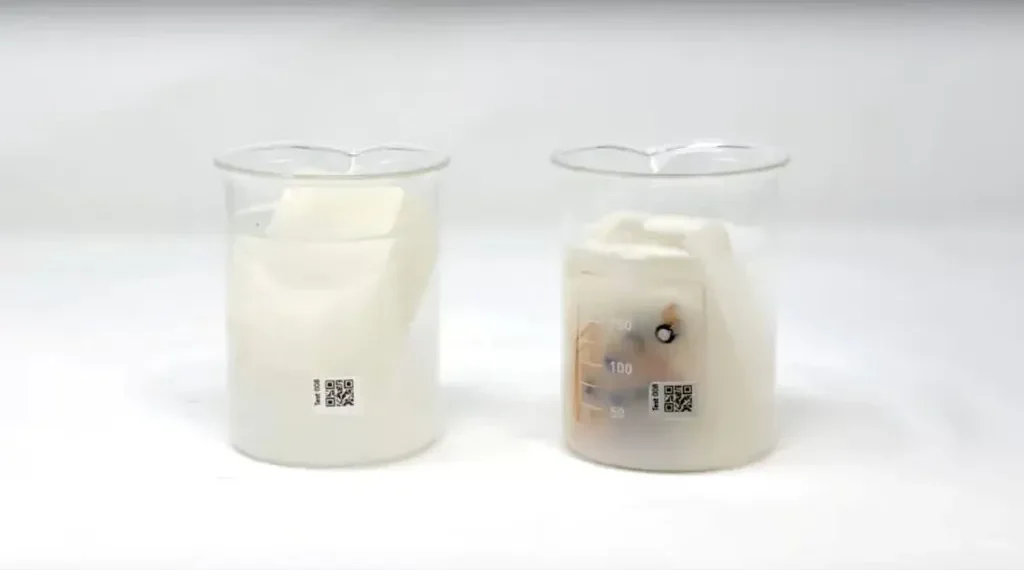

Once a single screw is removed, however, the integrity of the casing is compromised. Submerging the device then allows water to enter, triggering the dissolution process. After several hours, the casing breaks down into a cloudy liquid, leaving the electronic components intact.

Wangsaputra said the remaining liquid can be poured into household wastewater systems, where the material is expected to degrade further. The team acknowledges that full long-term studies on biodegradation are still ongoing.

First steps toward commercial use

Aquafade’s developers are currently focused on smaller, simpler products rather than complex consumer electronics. One of the first likely applications is single-use LED wristbands commonly distributed at concerts and large events.

“These are often worn once and thrown away by the thousands,” said Lee, adding that discussions are underway with a major supplier of such wristbands. The relatively simple construction of these devices makes them a practical testing ground for the technology.

In the longer term, the team hopes the material could be adapted for a broader range of electronics and even non-electronic products that rely on rigid plastic shells, from luggage and sunglasses to furniture and automotive interiors.

Cost and scale considerations

At present, Aquafade costs roughly twice as much as conventional ABS plastic, a standard material used in electronics casings. Wangsaputra argues that the impact on final product prices would be modest, accounting for an estimated 5% to 10% of overall manufacturing costs.

He also said costs could fall with mass production and wider adoption, particularly if manufacturers factor in savings from simpler recycling and reduced regulatory pressure over waste management.

Scientific caution and open questions

Independent experts say the concept is promising but stress that its environmental credentials will depend on detailed performance in real-world conditions.

Peter Edwards, emeritus professor of inorganic chemistry at the University of Oxford, described Aquafade as an interesting development but questioned whether the dissolved material could persist in the environment as microplastic if not fully degraded.

Michael Shaver, a professor of polymer science at the University of Manchester, noted that PVOH is already widely used and generally well managed in wastewater systems in developed countries. However, he said the interaction between the waterproof coating and the underlying soluble material requires closer scrutiny.

“The devil is in the details,” Shaver said, pointing out that electronic casings often need to meet strict standards for insulation, fire resistance, and long-term durability. Ensuring those properties while maintaining reliable biodegradation could prove to be the biggest technical hurdle.

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.