The Mystery of Stonehenge’s Lost Megaliths: Unraveling the Ancient Puzzle

Stonehenge, one of the most iconic and enigmatic landmarks in the world, has always fascinated historians, archaeologists, and visitors alike. However, the Stonehenge we see today is vastly different from the structure that existed over 4,500 years ago. The missing stones of this ancient monument raise compelling questions about its original form and purpose. Writer and archaeologist Mike Pitts delves into the mystery of Stonehenge’s long-lost megaliths.

A Midwinter Solstice at Stonehenge: A Glimpse of the Past

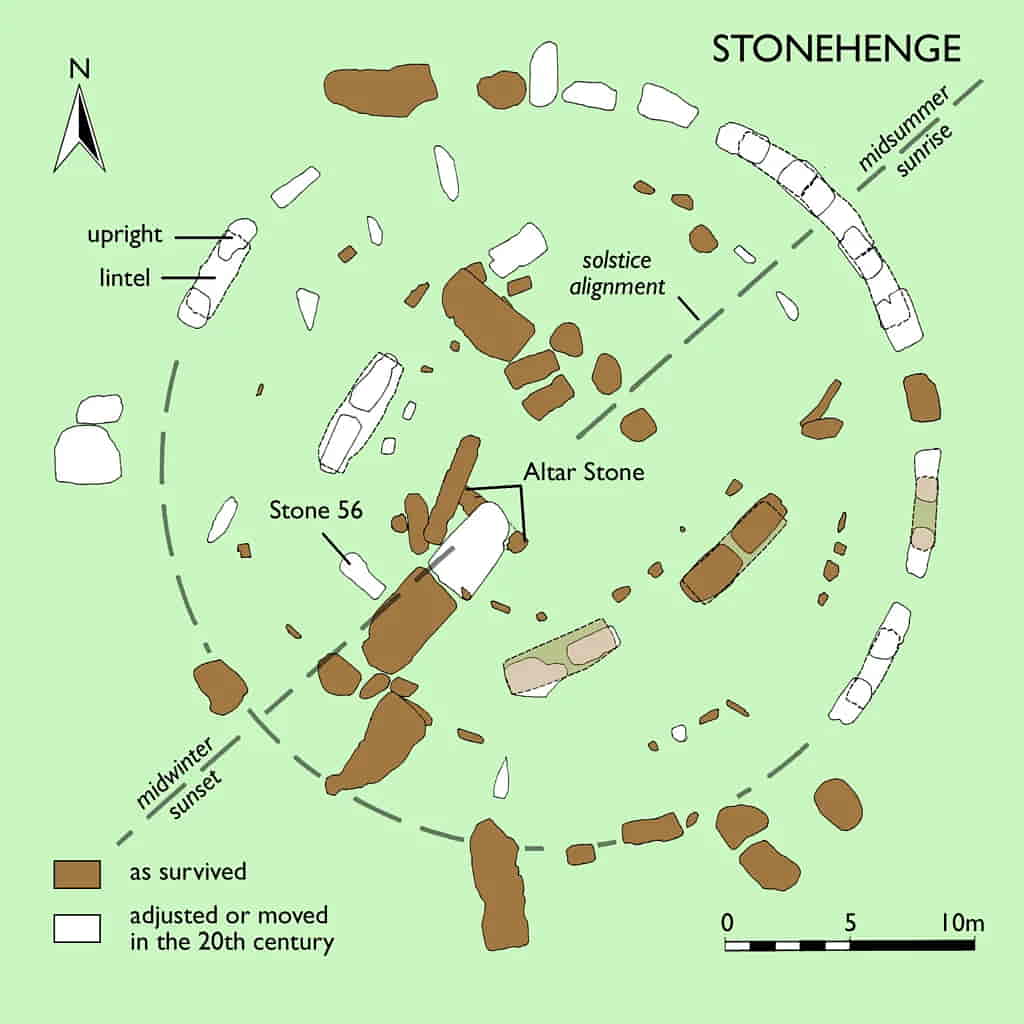

If you’re fortunate enough to be at Stonehenge on December 21st, with clear skies and the Sun setting just right, you’ll witness a remarkable phenomenon. Stand between the towering Heel Stone and the stone circle, and as the Sun disappears, the sight is awe-inspiring. The megaliths form a dramatic backdrop, with orange light filtering through gaps between the stones. It feels as though the monument itself swallows the Sun.

This alignment wasn’t a coincidence. Archaeologists, including myself, believe it was meticulously designed by the builders of Stonehenge. However, imagine experiencing this same sight 4,500 years ago. Back then, the spectacle would have been even grander, with up to six additional upright pairs of stones. Of the tallest and most intricately carved stones that once stood here, only one remains—Stone 56, its tenon exposed and useless. And that’s just one of many lost stones.

The Missing Stones: What Happened to Them?

The questions about the missing stones of Stonehenge are numerous and perplexing. Where did they go? Who took them down? Were they ever replaced? More importantly, can we reconstruct the original appearance of Stonehenge? Was the monument ever truly completed?

These are questions that have haunted archaeologists for centuries. While we may never have definitive answers, a series of excavations and discoveries over the years have brought us closer to solving the puzzle.

Stonehenge Through the Ages: A Complex History

What we see today at Stonehenge is largely unchanged since the 18th century when architect John Wood made the first accurate plan of the site. However, that doesn’t mean the monument has remained untouched. Between 1901 and 1964, many of the standing stones were moved to prevent them from falling. Some stones were straightened and secured with concrete, while others, having fallen in past centuries, were restored. This work, although necessary for preservation, revealed something unexpected: many stones were missing.

In 1666, antiquary John Aubrey noticed five “cavities in the ground” inside the circular bank and ditch surrounding the stone circle. He suggested these were the result of removed megaliths, hinting that an outer stone circle had once stood here, now entirely gone. Excavations in the 1920s uncovered 56 pits, known as the Aubrey Holes, which may have once held stones. More recently, some archaeologists believe that these holes are all that remains of a vast stone circle.

Excavations Reveal Clues About the Missing Stones

In the 1950s and 60s, further excavations near the standing stones uncovered more buried pits. These were likely once occupied by smaller megaliths. Other pits suggest that stones had been rearranged, creating a concentric oval and circle. Over time, these arrangements were altered, and many stones disappeared.

In 1979, I made a discovery that would deepen my understanding of Stonehenge. While excavating near the Heel Stone, I uncovered a pit where a large stone had once stood. The crushed chalk at the bottom of the pit indicated that this stone had once been part of a pair that framed the solstice alignment. This was a turning point for me as an archaeologist, as it demonstrated the monument’s complex history and the many changes it had undergone.

The Case of the Missing Stones: Why Were They Taken?

As archaeologists, we know that Stonehenge evolved over more than a thousand years. During this time, many stones were lost, broken, or removed. But why? One key factor is the composition of the stones themselves.

The large stones—sarsens—are made of hard, local sandstone and form the iconic structure of Stonehenge. The smaller stones, known as bluestones, are made from softer rock, with many brought from South Wales. Excavations have shown that the Aubrey Holes, for example, likely contained bluestones, as did another nearby circle, the stones of which may have been moved to Stonehenge.

Interestingly, reports from earlier centuries speak of visitors removing pieces of the stones as souvenirs. These stories were once dismissed as exaggerations, but in 2012, a laser survey of the megaliths revealed widespread damage, much of it caused by hammering. One particularly striking example is a sarsen lintel, which had been chiselled away to such an extent that it resembled a sausage roll compared to its sharp-edged counterparts.

The Slaughter Stone: A Clue to the Past?

One of the most mysterious pieces of Stonehenge is the Slaughter Stone, a large sarsen that lies on the ground between the Heel Stone and the stone circle. This stone shows signs of hammer and chisel marks, suggesting it may have been vandalized or repurposed in some way. Excavation near the Slaughter Stone revealed a pit that may have been used to remove or relocate the stone. Could this be evidence of further stone theft or destruction?

The Bluestones: A Story of Destruction and Healing

Unlike the sarsens, the bluestones are much more fragile and were often broken or damaged. Excavations suggest that some of this destruction occurred during Roman times or even in the Bronze Age, not long after the stones had been erected. One theory is that the stones were believed to have healing properties, and pieces may have been taken for their supposed magical or medicinal qualities.

In one remarkable case, the Altar Stone at the center of Stonehenge was found to have come from northern England or Scotland, not from South Wales as originally thought. Thanks to advanced geological techniques, researchers were able to track the Altar Stone’s origins, revealing the far-reaching history of this monument.

Conclusion: The Enduring Enigma of Stonehenge

Despite centuries of study, Stonehenge remains a monument of mystery. While we may never know exactly what happened to all the missing stones, ongoing archaeological research continues to shed new light on the monument’s complex history. The story of Stonehenge is one of creation, destruction, and reconstruction, with each new discovery adding another layer to the puzzle. And as we continue to explore, one thing is clear: Stonehenge’s mystery is far from over.

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.