A Medieval Scribe’s Mistake Hid an Epic Hero for Centuries — Until Now

A Long-Lost Tale Misread for Generations

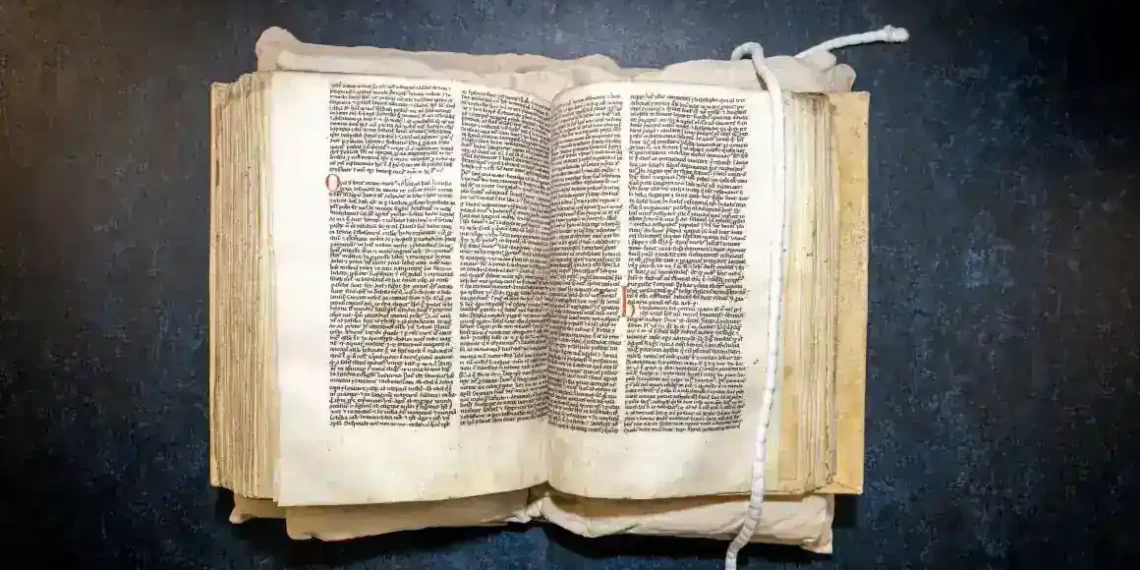

A newly published study from researchers at the University of Cambridge has uncovered a centuries-old mistake that changed how we understood a forgotten English legend. The error? A single miswritten letter by a medieval scribe.

The story at the center of this discovery is the Song of Wade — an epic once well-known in medieval England and even mentioned by famous poet Geoffrey Chaucer. But over time, the tale all but disappeared. Now, thanks to new research, we may finally understand what the story was really about — and it’s very different from what scholars once believed.

Rediscovering Wade: From Monster Hunter to Knightly Hero

The Song of Wade dates back to the 12th century and once captured the imaginations of medieval audiences. Though the full text has been lost for centuries, a fragment of it survived — quoted in a 13th-century Latin sermon written in Middle English.

That fragment led many scholars to believe the hero Wade fought magical creatures like elves and sprites. But according to Cambridge researchers Dr. Seb Falk and Dr. James Wade, the original meaning was mistranslated — all because a scribe accidentally wrote a “y” instead of a “w.”

The word once read as “ylues,” thought to mean “elves,” should actually be “wolves,” they say. The other term, “sprites,” may have been a mistaken reading of “sea-snakes.” Instead of a fantasy tale filled with monsters, the corrected version shows Wade facing human enemies and real-world dangers.

“He was more like a hero of chivalric romance,” Dr. Falk told CNN, comparing Wade to noble knights like Sir Launcelot or Sir Gawain.

Chaucer’s Mystery Reference Now Makes Sense

One big question has long puzzled scholars: why did Geoffrey Chaucer mention the Song of Wade in his courtly tales?

Chaucer includes brief references to Wade in The Merchant’s Tale and Troilus and Criseyde, works that focus on love, honor, and intrigue — not monster-slaying. The earlier interpretation of Wade as a Beowulf-like warrior didn’t fit.

Now, the updated understanding helps explain it. If Wade was a knightly hero in the romantic tradition, not a slayer of supernatural beasts, his presence in Chaucer’s chivalric stories makes more sense.

“Chaucer referring to a Beowulf-like ‘dark-age’ warrior in these moments is weird and confusing,” said Falk. “The idea that Chaucer is referring to a hero of medieval romance makes a lot more sense.”

The Clue Hidden in a Sermon

This fresh interpretation comes from a deeper look at the sermon that quoted the saga. The sermon focused on humility and warned against corrupt and violent leaders. Within this context, the quote — originally read as “Some are elves and some are sprites” — didn’t quite fit.

But the new reading — “Some are wolves… some are sea-snakes” — matches the sermon’s warning about dangerous men and human vices. It also lines up better with other metaphors in the text, where people are compared to animals.

Dr. James Wade said that looking at the excerpt in full context helped them reinterpret not just the quote, but the entire story. It offered a fresh view of how medieval culture blended storytelling with moral lessons.

When Mistakes Shape History

This discovery is also a reminder of how fragile old texts can be. Paleography — the study of ancient handwriting — often involves guessing at unclear words or faded letters. Even a small slip, like confusing “w” with “y,” can change the meaning of a whole legend.

Dr. Stephanie Trigg, an English literature professor at the University of Melbourne who wasn’t involved in the study, noted how rare it was for sermons to quote popular culture. That makes the Song of Wade reference all the more valuable for understanding medieval society.

“It helps disturb some traditional views about medieval piety,” Trigg told CNN. “The preacher clearly expected his audience to get the reference — like a medieval meme,” added Falk.

A Hero With a Fantastical Past

While this new interpretation pulls Wade away from fantasy creatures, that doesn’t mean his tale was entirely realistic. In other stories and local legends, Wade was said to be a giant, a dragon slayer, or even the son of a mermaid. Those details feel straight out of a Tolkien novel — and they probably helped the tale thrive in oral storytelling.

“In one romance text, it’s said that (Wade) slays a dragon,” Falk noted. Other records describe him as a giant or having magical parentage. These kinds of fantastical elements were common in medieval chivalric romances.

Even if the Song of Wade didn’t originally focus on magic, medieval storytellers likely added colorful details over time, blending reality and fantasy as they passed the legend along.

A Lost Legend Regained — At Least in Part

The full Song of Wade is still lost, and no complete version is known to exist. But this small correction — spotted through careful reading of a 13th-century sermon — gives us a clearer picture of Wade’s character and the world he lived in.

It also highlights how cultural memory works. Wade may have faded from public knowledge by the 18th century, but for hundreds of years, his story was widely recognized.

“By the eighteenth century there were no known surviving texts and nobody seemed to know the story,” Wade said. “Part of the enduring allure is the idea of something that was once part of common knowledge suddenly becoming ‘lost.’”

Thanks to this new research, Wade’s legacy — once misread and nearly forgotten — might just find a new audience today.

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.