WASHINGTON (AP) – Large-scale population data increasingly link late sleep-wake patterns to poorer cardiovascular health. The emerging question is not whether night owls are inherently unhealthy, but how circadian timing interacts with modern work, diet, and sleep norms to shape long-term heart risk.

Modern societies are largely organized around early schedules: standard workdays, school start times, medical appointments, and even social services are calibrated to morning-oriented routines. For people whose internal clocks run later — often described as “night owls” — this creates a structural mismatch between biology and daily life. New research suggests that this mismatch, rather than late activity itself, may help explain why night-oriented individuals show weaker cardiovascular health profiles.

A large observational study published in the Journal of the American Heart Association, based on UK Biobank data, adds weight to a growing body of evidence connecting circadian rhythm differences with heart disease risk. The findings raise broader questions about how flexible schedules, sleep regularity, and health behaviors intersect — and whether cardiovascular prevention strategies adequately account for biological diversity in sleep timing.

This analysis examines what the study found, how it fits with existing research, where uncertainty remains, and why the implications extend beyond individual sleep preferences to structural features of modern life.

What the new study shows

The study followed more than 300,000 middle-aged and older adults enrolled in the UK Biobank, a long-running health database that tracks medical outcomes, lifestyle factors, and self-reported traits, including chronotype — whether a person identifies as a morning type, evening type, or somewhere in between.

Participants were grouped broadly into early chronotypes (“larks”), late chronotypes (“night owls”), and intermediate types. About 8% identified as evening-oriented, roughly a quarter as morning-oriented, with the remainder falling in the middle.

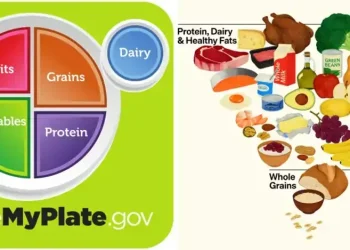

Over an average follow-up period of 14 years, evening types experienced a 16% higher risk of a first heart attack or stroke compared with the average population. They also scored worse on the American Heart Association’s “Life’s Essential 8” cardiovascular health metrics, which include physical activity, smoking, sleep duration, diet quality, body weight, blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar.

The researchers found that unhealthy behaviors — particularly smoking, shorter or irregular sleep, and poorer diet — appeared to account for much of the elevated risk. The pattern was especially pronounced among women, though the reasons for this sex difference were not fully explained.

Importantly, the authors emphasized that being a night owl is not a disease or destiny. Instead, they pointed to a persistent misalignment between internal circadian rhythms and external demands as a central explanatory factor.

Circadian rhythms and cardiovascular regulation

Circadian rhythms govern far more than sleep timing. They influence hormone secretion, blood pressure, heart rate variability, glucose metabolism, and inflammatory processes — all of which are relevant to cardiovascular health.

Blood pressure, for example, normally dips at night and rises in the morning. Disruptions to this rhythm, such as blunted nighttime dipping, are associated with higher risks of heart attack and stroke. Similarly, insulin sensitivity follows a daily cycle, typically peaking earlier in the day and declining at night.

For people whose biological night extends later into the morning, early meals, early commutes, and early work demands may occur during what their bodies interpret as a low-metabolic-efficiency period. Over time, this may contribute to weight gain, impaired glucose control, and elevated cardiovascular risk markers.

Experts who were not involved in the study note that circadian misalignment can affect multiple systems simultaneously. Kristen Knutson of Northwestern University, who contributed to recent American Heart Association guidance on circadian rhythms, has previously highlighted that sleep timing, not just sleep duration, matters for cardiometabolic health.

Behavior versus biology: untangling the drivers of risk

One of the key analytical challenges is distinguishing between biological effects of late chronotype and behavioral patterns associated with it. Evening-oriented individuals, on average, are more likely to smoke, exercise less regularly, eat later, and sleep fewer hours on workdays — all independent risk factors for heart disease.

The UK Biobank analysis suggests that these behaviors explain a substantial portion of the observed risk difference. When adjustments were made for lifestyle factors, the association between evening chronotype and cardiovascular events weakened, though it did not disappear entirely.

This leaves open several interpretations. One is that late chronotype indirectly increases risk by making healthy behaviors harder to maintain in a morning-oriented society. Another is that circadian timing itself may have modest independent effects on cardiovascular physiology, even when behaviors are controlled.

Crucially, the study design cannot establish causality. Chronotype was self-reported, behaviors were measured imperfectly, and unmeasured confounders may still play a role. Genetic studies have suggested that chronotype has a heritable component, but genetics alone does not dictate outcomes.

Why women may be affected differently

The finding that female night owls showed particularly poor cardiovascular health metrics deserves attention, though it should be interpreted cautiously. Women’s cardiovascular risk profiles are influenced by hormonal cycles, menopause timing, caregiving responsibilities, and occupational patterns, all of which may interact with sleep timing.

Some researchers have suggested that women may experience greater sleep disruption due to caregiving roles that conflict with late chronotypes, leading to chronic sleep debt. Others note that women’s cardiovascular risk has historically been under-recognized and may manifest differently than in men.

The UK Biobank data cannot fully disentangle these factors. Still, the sex-specific signal aligns with broader calls from cardiology organizations to tailor prevention strategies more precisely, rather than assuming uniform risk pathways.

Structural schedules and the “morning person’s world”

A recurring theme in circadian research is that social schedules are not biologically neutral. Standardized start times for work and school effectively privilege early chronotypes, while evening types operate under chronic time pressure.

This “social jet lag” — the gap between biological time and social time — has been linked in previous studies to obesity, metabolic syndrome, depression, and cardiovascular risk factors. Unlike travel-related jet lag, social jet lag can persist for decades.

The study’s authors argue that the health burden observed among night owls is not an inherent flaw of late chronotypes, but a predictable outcome of prolonged misalignment. In that sense, cardiovascular risk emerges as a systemic issue rather than an individual failing.

Some employers and schools have experimented with later start times or flexible scheduling, often reporting improvements in sleep duration and well-being. However, evidence on long-term cardiovascular outcomes from such interventions remains limited.

What remains uncertain

Despite the scale of the dataset, several uncertainties remain. The study could not track precisely how participants spent their evenings or nights, nor could it measure circadian phase directly through biological markers such as melatonin timing.

Dietary quality and physical activity were assessed through self-report, which can introduce bias. The cohort also skewed older and healthier than the general population, potentially limiting generalizability to younger adults or shift workers, whose circadian disruption is often more severe.

It is also unclear how much risk could be reduced if evening chronotypes successfully adopted healthier behaviors while maintaining late schedules. Whether alignment can be improved without shifting sleep timing remains an open question.

Implications for prevention and policy

From a public health perspective, the findings reinforce the idea that cardiovascular prevention cannot rely solely on universal advice detached from daily realities. Recommendations to “sleep earlier” may be unrealistic for many evening-oriented individuals, particularly in creative, technical, or service-sector roles that favor later hours.

Instead, researchers increasingly emphasize consistency, smoking cessation, diet quality, and physical activity as priorities that apply across chronotypes. Regular sleep-wake timing, even if late, may be less harmful than irregular schedules with large weekday-weekend swings.

At a policy level, the research adds to debates about flexible work arrangements, later school start times, and the health costs of rigid scheduling norms. While such changes are unlikely to be justified on cardiovascular grounds alone, they intersect with broader concerns about productivity, equity, and well-being.

A conditional conclusion

The evidence to date suggests that being a night owl is associated with poorer cardiovascular health outcomes, largely because late chronotypes are forced to operate in systems designed for early risers. The risk is not inevitable, but it is structured.

Rather than framing evening orientation as a personal liability, the research points toward a more nuanced understanding of how biology, behavior, and social organization interact. As cardiovascular prevention efforts evolve, accommodating circadian diversity may become less a lifestyle preference and more a matter of public health relevance.

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.