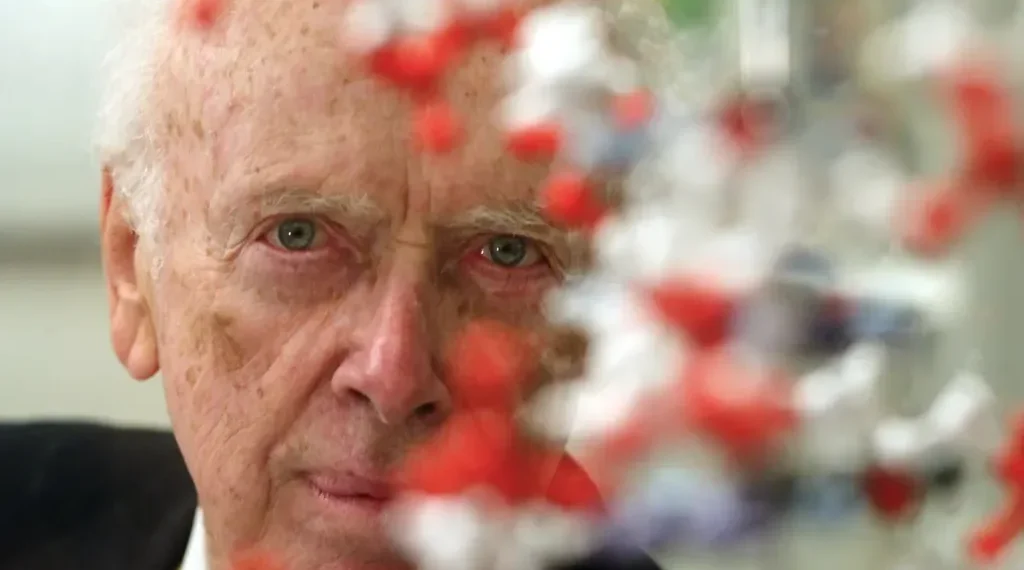

James Watson, DNA Pioneer and Controversial Figure in Modern Science, Dies at 97

James D. Watson, the American molecular biologist whose co-discovery of DNA’s double-helix structure revolutionized modern science and medicine, has died at the age of 97. His son confirmed that Watson passed away in hospice care after a brief illness, marking the end of a remarkable yet turbulent career that reshaped how humanity understands life itself.

Watson’s work in the early 1950s, completed alongside British physicist Francis Crick, revealed the molecular architecture of DNA — a discovery that became the foundation of genetics, forensics, and modern biotechnology. But his later years were overshadowed by divisive remarks about race and intelligence, which drew widespread condemnation from the scientific community.

The Discovery That Changed Biology Forever

In 1953, at just 24 years old, James Watson and Francis Crick unveiled the now-iconic double-helix model of deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA. Their finding — that genetic information is encoded in paired strands twisted like a spiral staircase — unlocked the mechanism by which life reproduces and evolves.

The discovery, made at Cambridge University’s Cavendish Laboratory, was based partly on X-ray diffraction data produced by Rosalind Franklin and her student Raymond Gosling. The model explained how DNA replicates during cell division, how traits are inherited, and how mutations occur.

The discovery earned Watson, Crick, and physicist Maurice Wilkins the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, cementing their place among the most influential scientists of the 20th century.

From the Lab to Global Recognition

Even outside scientific circles, the double helix became a universal symbol of discovery. It appeared in art, advertising, and education — from Salvador Dalí’s surrealist works to postage stamps and logos.

Watson himself became one of the most recognizable figures in biology. He later said, “Francis Crick and I made the discovery of the century, that was pretty clear,” acknowledging that they could not have foreseen how their work would transform medicine, genetics, and society.

Their breakthrough laid the groundwork for everything from gene therapy and genetic engineering to DNA fingerprinting used in law enforcement and ancestry tracing. It also raised ethical questions about how far science should go in manipulating life’s blueprint.

A Career of Influence and Ambition

Watson never made another discovery as monumental as the double helix, but his influence on science continued for decades. After teaching at Harvard University, where he helped establish its molecular biology program, he became director of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) in New York in 1968.

Under his leadership, CSHL grew into a global hub for genetics and cancer research. He was instrumental in attracting funding, mentoring young scientists, and advocating for bold research initiatives.

Between 1988 and 1992, Watson headed the U.S. Human Genome Project, an ambitious government-led effort to map the entire sequence of human DNA. He also championed the inclusion of ethics research within the project, later calling that decision “probably the wisest thing I’ve done over the past decade.”

In 2000, Watson joined President Bill Clinton at the White House for the announcement of the project’s first major milestone — a working draft of the human genome covering about 90 percent of human genes.

The Personal Drive Behind His Pursuit of Genetics

Watson’s interest in genetics was deeply personal. His son Rufus had been hospitalized as a young man with symptoms once thought to be related to schizophrenia. Understanding human DNA, Watson believed, might one day explain the biological roots of such disorders and lead to better treatments.

In 2007, he became one of the first people to have his entire genome sequenced — a fitting tribute to the man who had helped uncover life’s fundamental code more than half a century earlier.

Controversy and a Tarnished Reputation

Despite his scientific brilliance, Watson’s later years were marked by controversy. In 2007, the Sunday Times of London quoted him as suggesting that people of African descent were inherently less intelligent than others — remarks that were widely condemned as racist and scientifically unfounded.

Following global backlash, Watson apologized but was suspended from his position as chancellor of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and retired shortly after.

In a 2019 documentary, when asked if his views had changed, Watson said they had not. The laboratory subsequently revoked his honorary titles, calling his statements “reprehensible” and “unsupported by science.”

Dr. Francis Collins, then director of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, described Watson’s comments as “profoundly misguided and deeply hurtful,” though he praised his scientific achievements.

A Complex and Contradictory Legacy

Watson’s mixture of genius and controversy made him one of the most polarizing figures in modern science. He often dismissed political correctness, once writing in his 1968 memoir The Double Helix that “a goodly number of scientists are not only narrow-minded and dull, but also just stupid.”

For Watson, scientific progress required boldness. “To make a huge success,” he wrote, “a scientist has to be prepared to get into deep trouble.”

He also faced criticism for how he portrayed Rosalind Franklin in The Double Helix, reflecting gender biases that dominated science in the mid-20th century. Franklin, whose X-ray images were essential to decoding DNA’s structure, died in 1958 and was not eligible for the Nobel Prize.

A Life of Discovery and Contradiction

James Dewey Watson was born in Chicago on April 6, 1928, to a family that valued learning and reason. A prodigy, he entered the University of Chicago at 15 and earned his Ph.D. in zoology at Indiana University by age 22.

Initially fascinated by birds, Watson’s interests shifted toward genetics after reading about the role of genes as the essence of life. “If the gene is the essence of life, I want to know more about it,” he recalled.

In Europe, he encountered emerging X-ray crystallography research that inspired his quest to decode DNA’s structure. He and Crick ultimately pieced together the molecule’s form using cardboard models in 1953. “It’s so beautiful,” Watson later said of the moment the structure clicked into place.

Enduring Impact on Science

Watson’s contributions transformed biology into a molecular science. Bruce Stillman, president of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, said the double helix ranks among the “three most important discoveries in the history of biology,” alongside Darwin’s theory of evolution and Mendel’s laws of heredity.

Though his public standing declined due to his remarks, his scientific achievements remain a cornerstone of modern genetics. As one colleague once noted, “You don’t need a building named after you when you have the double helix.”

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.