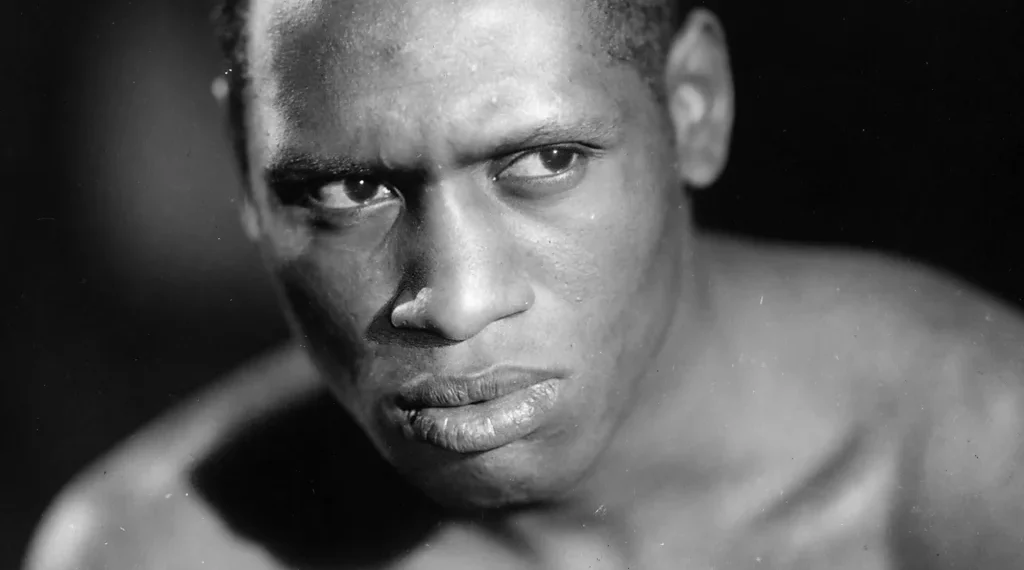

Paul Robeson once stood at the centre of American public life. He was a leading stage and film actor, a best-selling singer, and one of the most gifted athletes of his generation. By the late 1940s, however, he had become one of the most deliberately removed figures in the nation’s cultural memory.

His life followed a sharp and revealing arc. The rise was rapid and widely celebrated. The fall, by contrast, was slow, systematic, and driven by politics rather than scandal. As Cold War anti-communism hardened into policy, Robeson’s views on race, labour, and global justice placed him on a collision course with the US establishment.

As a result, a sustained campaign of exclusion followed. It stripped him of his income, his passport, and, for many years, his place in the American story.

A patriotic anthem at the height of fame

In 1939, Robeson reached the peak of his popularity with Ballad for Americans. The 10-minute patriotic cantata presented an inclusive vision of the United States, blending history, struggle, and shared identity.

He first performed the piece on a national CBS radio broadcast. The response was immediate. Audience applause lasted more than 20 minutes, while listeners flooded the network with letters and calls. Because of the demand, broadcasters replayed the programme repeatedly, and the recording became a commercial success.

At that point, Robeson was already a household name. Ballad for Americans pushed him even further into the national spotlight. Within ten years, however, that visibility had almost entirely vanished.

An exceptional beginning

Paul Robeson was born in 1898 in Princeton, New Jersey, the youngest of five children. After his mother died in a house fire, his father, a pastor, raised the family alone.

From an early age, Robeson showed rare ability. At Rutgers University, he excelled in both academics and sport. He graduated with top honours, delivered the class oration, and earned 15 varsity letters across several disciplines.

Football brought him national recognition. He was named to the All-American first team twice and later played professionally. That income helped fund his studies at Columbia Law School. Walter Camp, one of the era’s leading football authorities, later described Robeson as among the finest defensive players of his time.

Turning away from the law

While studying law, Robeson lived in Harlem during the Harlem Renaissance. Alongside his academic work, he began acting and singing.

Shortly after graduating, he left the legal profession altogether. The decision followed an incident at his law firm, where a white secretary refused to take dictation from him. Rather than accept the insult, Robeson chose another path.

With early financial support from his wife, Eslanda Robeson, he committed himself fully to performance. Success followed quickly. He starred in Eugene O’Neill’s All God’s Chillun Got Wings and The Emperor Jones. His recordings of spirituals reached wide audiences, while his performance of Ol’ Man River in Show Boat earned critical praise.

Film roles soon followed. By the early 1930s, Robeson had become one of the most prominent Black performers in American entertainment.

Global acclaim

Robeson’s reputation soon spread beyond the United States. In 1930, he played Othello on a major London stage, becoming the first Black actor to do so there in decades.

By the mid-1930s, he was a global figure. American publications praised him as a cultural ambassador and a symbol of Black achievement. At the same time, audiences across Europe and North America filled theatres to see him perform.

By the early 1940s, his position appeared secure. He performed for tens of thousands at the Hollywood Bowl. Collier’s magazine named him “America’s No. 1 Negro Entertainer.” His popularity crossed racial and political lines, and his earnings reflected that success.

Politics move to the foreground

Behind the scenes, Robeson’s political views continued to deepen. Travel exposed him to labour movements, anti-fascist campaigns, and colonial resistance. He supported Welsh miners and raised funds for Republican fighters during the Spanish Civil War.

At home, he refused to perform before segregated audiences. He joined union picket lines and spoke openly against racial injustice. In addition, he studied African languages and Marxist theory, and he expressed admiration for aspects of the Soviet Union’s public position on racial equality.

For several years, these views attracted criticism but caused little direct harm. That balance shifted in April 1949.

The Paris speech that changed everything

Robeson addressed the World Congress of Partisans for Peace in Paris as Cold War tensions intensified. During his remarks, he argued that African Americans should not be expected to fight in a war for a government that denied them full rights at home.

The reaction in the United States was swift. Media coverage framed the speech as disloyal, while political figures condemned him across party lines. Former allies stepped back, and conservative critics called for his removal from public life.

From that point on, the consequences escalated.

Blacklisting and disappearance

Later in 1949, violent protests disrupted two of Robeson’s concerts near Peekskill, New York. Rioters attacked audience members and overturned cars, while police largely failed to intervene.

Although public figures condemned the violence, quieter forms of punishment followed. In 1950, NBC cancelled a planned television appearance after pressure from veterans’ groups. Soon after, the State Department revoked Robeson’s passport.

That decision cut him off from overseas audiences, where he remained popular. Within the United States, concert halls, broadcasters, and record labels closed their doors. His career collapsed almost entirely.

His income fell sharply. His music disappeared from radio playlists and store shelves. Schools removed references to his work, while publishers erased his name from books that once praised him.

A singular figure in the Red Scare

Robeson was not the only person blacklisted during the Red Scare. Even so, his prominence made the scale of his erasure unusual. Historian Ellen Schrecker later noted that few individuals faced such broad censorship.

As a Black artist who linked civil rights to global labour and anti-colonial movements, Robeson challenged Cold War boundaries. In turn, the political system treated him as a unique threat.

In 1956, he appeared before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. He rejected the committee’s authority and challenged its definition of patriotism. The appearance did nothing to restore his career.

Final years and historical reassessment

The government returned Robeson’s passport in 1959. He resumed limited international travel, but years of pressure had taken a toll. Illness and depression increasingly limited his public appearances.

By the mid-1960s, he had withdrawn almost entirely from public life. In 1973, he delivered a final recorded message at a tribute event in New York, reaffirming his commitment to racial justice and global peace.

Paul Robeson died in January 1976. For decades, his legacy remained incomplete and contested.

Today, historians increasingly view him as both a cultural giant and a warning from history. His life shows how fear and ideology can silence even the most celebrated voices — and how easily a nation can erase its own icons.

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.