The Psychology Behind “The Traitors”: Why Deception Keeps Viewers Hooked

Published: October 11, 2025, 22:10 EDT

The BBC’s The Traitors: Celebrity Edition has captivated audiences once again with its mix of deception, manipulation, and emotional tension. Behind the game’s betrayals lies a deeper psychological story about why people lie — and why millions can’t look away.

Deception as Human Nature

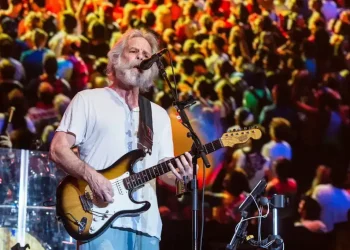

At its core, The Traitors is a game built on lies. Contestants must conceal, deceive, and betray — all under the pretense of cooperation. In the new celebrity version, comedian Alan Carr kicked off the season with the first “murder,” eliminating singer Paloma Faith, his close friend, in a dramatic twist that blurred the line between play and personal trust.

According to Professor Richard Wiseman, a psychologist at the University of Hertfordshire, such intrigue mirrors everyday life. “We’re constantly figuring out who’s being honest with us — friends, partners, colleagues,” he told BBC News. Deception, he said, is not just common but “part of our DNA.” Children begin lying as soon as they master language, and society depends on a balance between truth and concealment.

“If we were radically honest all the time, we’d fall apart as a society,” Wiseman explained. “On one level, deception actually holds us together.”

Why Audiences Love Watching People Lie

The fascination with deceit isn’t new, but The Traitors amplifies it in a safe, entertaining way. Viewers watch alliances form and crumble, seeing moral boundaries tested in real time. For Wiseman, it’s the same curiosity that drives interest in magic, illusion, and mystery — the thrill of trying to detect the lie before it’s revealed.

On-screen, identifying liars is harder than it seems. “We’re good at spotting deception in people we know well,” Wiseman said. “But with strangers, it’s much more difficult.”

This explains why contestants like Kate Garraway, accused of overacting during tense moments, can appear suspicious simply for being expressive. “To know whether someone’s lying, you have to know how they behave normally,” Wiseman added.

Silence Speaks Louder Than Words

While contestants often analyze speech and gestures, Wiseman suggests they might be looking in the wrong places. “The best indicators aren’t what people say, but what they don’t say,” he noted. Liars, he explained, tend to be quieter and more controlled — a challenge for celebrities accustomed to attention.

Singer Cat Burns, one of this season’s secret traitors, revealed her strategy early on: “I plan to lay low and go under the radar.” So far, that restraint has worked.

Wiseman added that good liars are typically intelligent and observant — traits common in professions such as sales, politics, and entertainment. “Alan Carr and Jonathan Ross are skilled interviewers,” he said. “They know how to read people — and how to be elusive themselves.”

Can Actors Really Lie Better?

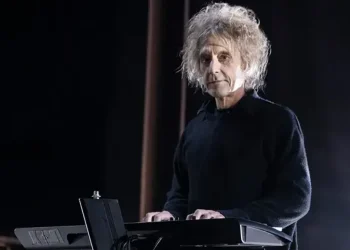

The question of whether performers make better liars divides opinion. Actor Stephen Fry, a “faithful” contestant this season, told Radio Times that “actors are terrible liars” because their job is to “tell emotional truth.” But fellow cast members and past contestants disagree.

Former finalist Alexander Dragonetti told BBC News that while actors can perform convincingly, maintaining deception over multiple days is “the test of a lifetime.” “You have to be consistent,” he said. “If anyone spots even a tiny crack, they’ll think you’re playing a game — and you’re gone.”

The Illusion of Cooperation

Forensic psychologist Dr. Susan Young sees the show as more than entertainment. It’s “a social experiment,” she said, exposing “the illusion of cooperation” that exists in many parts of real life.

“Everyone must lie to survive, but lying also corrodes the team,” Young explained. “That tension mirrors what happens in workplaces, politics, and friendships under stress.” Viewers, she added, act as “voyeurs of morality,” eager to see good people bend their ethics when incentives shift.

Her analysis highlights a central paradox: deception both sustains and destroys human relationships. The game simply magnifies that truth.

Celebrity Status Means Nothing Inside the Game

Despite its star-studded cast, fame offers little protection inside The Traitors’ castle walls. Caroline Frost, TV editor at Radio Times, said the new celebrity edition strips contestants of their public personas. “By nightfall, their reputations don’t count,” she said. “The further they get into the game, the less their fame matters.”

Frost praised the show’s producers for making Carr one of the traitors. “He’s so naturally open and talkative that you’d never expect him to keep a secret,” she said. “That makes his deception all the more powerful — and entertaining.”

Even Carr seemed conflicted after eliminating his friend Paloma Faith. But fellow traitor Jonathan Ross reminded him, “You’re not a bad person. You’re a good traitor.”

A Mirror to Human Psychology

Beyond its dramatic reveals and theatrical betrayals, The Traitors resonates because it reflects something deeply human. The show explores how honesty, trust, and self-interest coexist — and collide — under pressure.

As Wiseman summarized, deception may not just be part of the game; it may be the glue that binds us together. “It fascinates us because it’s us,” he said.

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.