The de Havilland Comet: Aviation’s first jetliner and its fatal legacy

Written July 30, 2025 – 16:00 EDT

The de Havilland Comet 1A launched the world into the jet age in 1952 with unmatched speed and luxury. But what began as a revolutionary leap in air travel ended in tragedy, as fatal design flaws brought its career to a premature end. Now, decades later, a dedicated restoration team has brought a Comet back to life — not in the skies, but in a museum, where it serves as both a tribute and a cautionary tale.

A revolutionary takeoff: The birth of jet travel

On May 2, 1952, a sleek, jet-powered aircraft took off from London Airport (now Heathrow), carrying fare-paying passengers bound for Johannesburg. That aircraft — the de Havilland DH106 Comet 1A — was the world’s first commercial jetliner.

With a total flight time of 23 hours and five scheduled stops, it was still significantly faster and more comfortable than the propeller-driven airliners of the time, like the Lockheed Constellation. The Comet introduced pressurized cabins and a quieter, smoother ride, redefining the commercial flying experience.

Designed and manufactured by British aviation pioneer Geoffrey de Havilland’s company, the Comet marked a major milestone: Britain, not the United States, had taken the lead in the jet age.

A luxury vessel in the sky

The early Comets offered a level of comfort that remains impressive even by today’s standards. Separate bathrooms for men and women, ashtrays in every seat, generous legroom, and gourmet meals served on real plates were standard. Even the lighting fixtures and seat finishes were carefully crafted to project opulence.

Publicity photos from the 1950s show passengers in elegant attire, sipping cocktails or chatting over wooden tables in a first-class lounge area. Tickets were expensive — a one-way fare from London to Johannesburg cost about £175, the equivalent of nearly £4,400 ($6,000) today. Air travel, at that point, was strictly for the wealthy.

Fatal flaws in a pioneering design

But the Comet’s pioneering technology masked dangerous weaknesses. The aircraft’s four de Havilland Ghost turbojet engines were embedded in the wings — an innovative decision, but one that increased structural strain and made maintenance difficult. The aircraft’s square windows, designed for style and visibility, proved catastrophic under repeated pressurization at high altitudes.

The problems started to surface within a year of the Comet’s debut:

- March 3, 1953: A Canadian Pacific Airlines Comet crashed during takeoff in Pakistan, killing 11.

- May 2, 1953: A BOAC Comet crashed on takeoff from Calcutta, India, killing 43.

- January 10, 1954: A Comet flying to Rome disintegrated midair, killing 35.

- April 8, 1954: Another midair breakup occurred, killing 21.

Investigators eventually determined that repeated cabin pressurization caused metal fatigue, particularly around rivets and window corners. These design oversights turned the Comet from a symbol of innovation into a tragic engineering lesson. The entire fleet was grounded.

Painstaking restoration at the de Havilland Aircraft Museum

The story could have ended there. But at the de Havilland Aircraft Museum, located northwest of London near the M25 motorway, aviation enthusiasts have resurrected the Comet — not to fly, but to showcase its legacy.

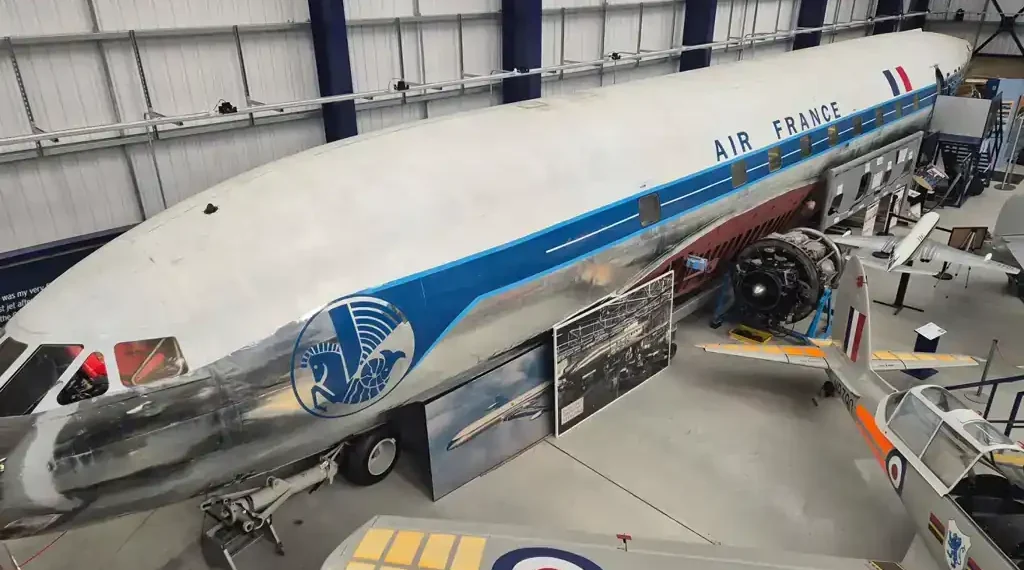

The museum’s Comet, painted in a vintage Air France livery, is a restored fuselage that arrived at the museum in 1985 as a bare metal shell. “It looked very sad,” says Eddie Walsh, a retired engineer and lead volunteer on the restoration project. “It was just a tube.”

Over decades, volunteers restored the interior to near-original condition using period materials and 3D-printed components. Inside, visitors can now walk through a cabin recreated with 1950s seats, wood-trimmed tray tables, and retro fixtures — complete with light buttons labeled “steward.”

Though the wings are missing, the aircraft remains a centerpiece of the museum, sharing space with other de Havilland icons like the WWII-era Mosquito, the Vampire jet fighter, and the Horsa glider.

The engineering that changed everything

Visitors can see firsthand the features that made the Comet both groundbreaking and fatally flawed. The rectangular windows, now cut away on one side of the fuselage, illustrate the structural weak points. Nearby, a test panel used in high-pressure water tank experiments shows how early airframes cracked under pressure.

These engineering tests — and the tragedies that prompted them — led to major reforms in aircraft design. Future jets adopted rounded windows and thicker, more flexible fuselage skins. The research done on the Comet’s failures helped ensure the safety of every commercial jet that followed.

The jet age takes off — without de Havilland

Though later versions of the Comet (notably the Comet 4) addressed many flaws and flew commercially into the 1980s, the damage to its reputation was done. By the time the Comet returned to service in 1958, Boeing had introduced the 707, and Douglas had launched the DC-8 — aircraft that quickly dominated long-haul routes.

De Havilland, once a world leader, was absorbed into Hawker Siddeley in the 1960s. While the British company faded from commercial aviation, its contributions — including the innovation and hard lessons of the Comet — live on in every modern airliner.

Legacy of the Comet

Despite its tragic end, the de Havilland Comet remains a pivotal aircraft in aviation history. It proved that jet-powered passenger travel was possible, even if the technology wasn’t yet mature.

“It was too high, too fast, too soon,” Walsh says. “But without someone taking that leap, nobody else would have followed.”

The restored Comet at the de Havilland Aircraft Museum stands as both a monument to the bold ambitions of postwar engineering and a reminder of the lives lost in the pursuit of progress.

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.