The final craftswoman: Preserving Hong Kong’s hand-carved mahjong legacy

July 25, 2025 – 10:56 AM

In a rapidly modernizing corner of Hong Kong, one woman continues to carve out a living—literally—from a centuries-old tradition. Ho Sau-Mei, one of the last hand-carving mahjong tile artisans in the city, works from a tiny storefront in Hung Hom, surrounded by high-rise developments and passing double-decker buses. But her presence stands as a testament to cultural endurance in a time of change.

A life dedicated to tradition

At 68, Ho’s hands remain steady, though the years have taken their toll. “My eyesight is fading, and my hands are sore,” she admits, eyes fixed on the tiny plastic tile beneath her carving tool. Each tile—no bigger than a postage stamp—is hand-etched with intricate Chinese characters or delicate floral patterns, part of the 144-piece set central to the beloved Chinese game mahjong.

Ho’s dedication to the craft spans over five decades. She began learning at 13 under her father, who founded Kam Fat Mahjong in 1962. During Hong Kong’s manufacturing boom in the 1970s and 80s, visiting master craftsmen shared skills and passed along techniques. Today, Ho is not only one of the last remaining artisans but the only woman still practicing the trade in Hong Kong.

The game behind the craft

Mahjong is more than a game—it is a cultural ritual across Chinese communities. Played with four players, it’s often compared to rummy. Families gather during the Lunar New Year to play, and among older generations, it remains a daily pastime. Its appeal spans entertainment and tradition.

Historically, mahjong tiles were handcrafted from bamboo, bone, or ivory. Carvers would cut, polish, engrave, and hand-paint each piece. But times have changed. Today, most tiles are mass-produced in factories in mainland China, sold online for as little as $10.

In 2014, Hong Kong’s government listed mahjong tile carving as part of its “intangible cultural heritage,” an effort to preserve traditional crafts. Yet few artisans remain.

A vanishing trade in a transforming city

From her dimly lit shop on Bulkeley Street, Ho’s world is no more than two meters wide. A faded glass display case rises to the ceiling, filled with novelty tile sets and old photos. A small shrine glows quietly in the background as Ho carves, the street noise blending into her focused rhythm.

Her routine hasn’t changed much, even as skyscrapers have replaced many old businesses around her. By 10 a.m., she’s seated at her shop, tools laid out, ready to work. These days, she only works a few hours in the morning. “I don’t have the stamina anymore,” she says. “But I’d be bored if I stopped completely.”

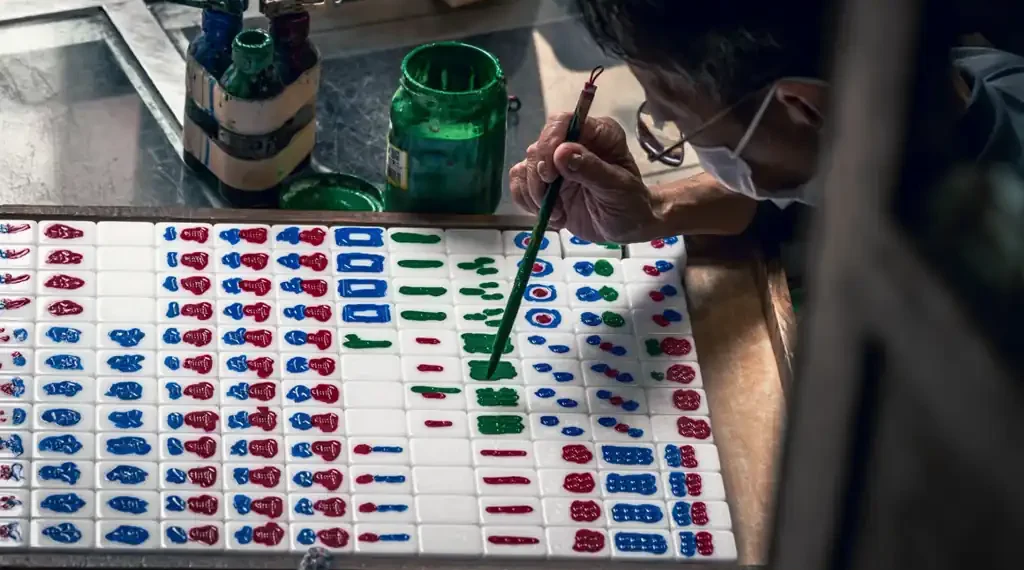

A full mahjong set, priced at around $245, takes her 10 to 14 days to finish. Every piece is meticulously shaped and carved by hand, a process involving a set of specialized tools. One tool resembles a large corkscrew used to drill dot patterns; others vary in tip and size to create different strokes.

After engraving, Ho uses vintage glass jars of red, green, and blue paint to fill in the etched designs. “Don’t go away, this part is fast,” she says with a grin, brushing color across the tiles with practiced ease.

A fully analogue business

Despite her remarkable craftsmanship, Ho operates without a website or digital ordering system. Orders are taken by phone or in person, and she logs them in a tattered notebook with no structure or tracking. When a British customer calls to check on an order, Ho needs help translating—and flipping through pages of scribbled notes to confirm the delivery status.

“I can’t keep up with the orders,” she says. “I’m not a machine. It’s really down to luck and timing.”

Once the tiles are painted and left to dry, she starts closing shop for the day. “I’m still a woman,” she jokes. “I have groceries to buy and a house to run.”

Modern pressures and changing times

Hong Kong’s transformation from a manufacturing hub to a financial center in the 1990s reshaped its economic landscape. Today, machine-carved tiles dominate the market, especially from mainland producers. Even the licensed mahjong parlor near Ho’s shop uses factory-made sets.

While Ho once played mahjong frequently with family, she rarely has time now. Sometimes, old friends invite her to join games—but most of her hours are spent alone, focused on her craft.

She doesn’t plan to pass her knowledge down. “I was never interested in teaching,” Ho says plainly. Over the years, cultural organizations and artists have approached her about mentorship and demonstrations, but she always declined. “I work at my own pace. That’s how I like it.”

Despite this, Ho regularly welcomes curious visitors—journalists, students, and tourists—eager to document her rare skill. “People are becoming more aware of this dying craft,” she acknowledges. “That’s good.”

Still, her hands ache more now. Her vision blurs more easily. “I don’t know how much longer I can do this,” she admits. “But as long as I can still hold the tools, I’ll keep going.”

A fading but enduring legacy

Every morning, Ho returns to her stool, laying out her tools and tiles. She continues carving by hand what most machines now mass-produce. With each stroke, she preserves a piece of Hong Kong’s heritage.

Even if no apprentice steps in, her work leaves a lasting impression—not only on the tiles she creates, but on the cultural fabric of the city.

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.