The Dark History Behind the Iconic Bison Skull Mountain Photo

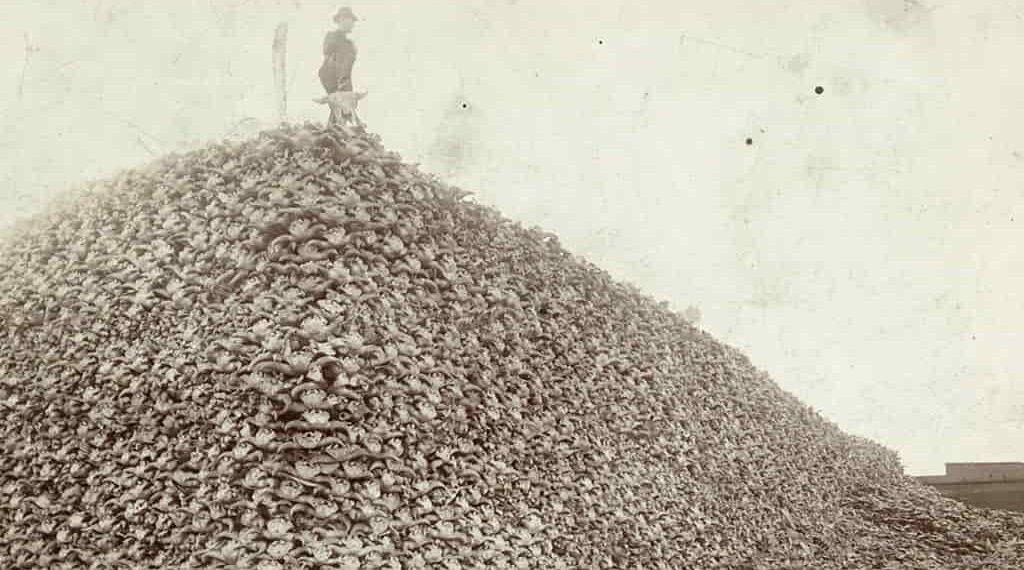

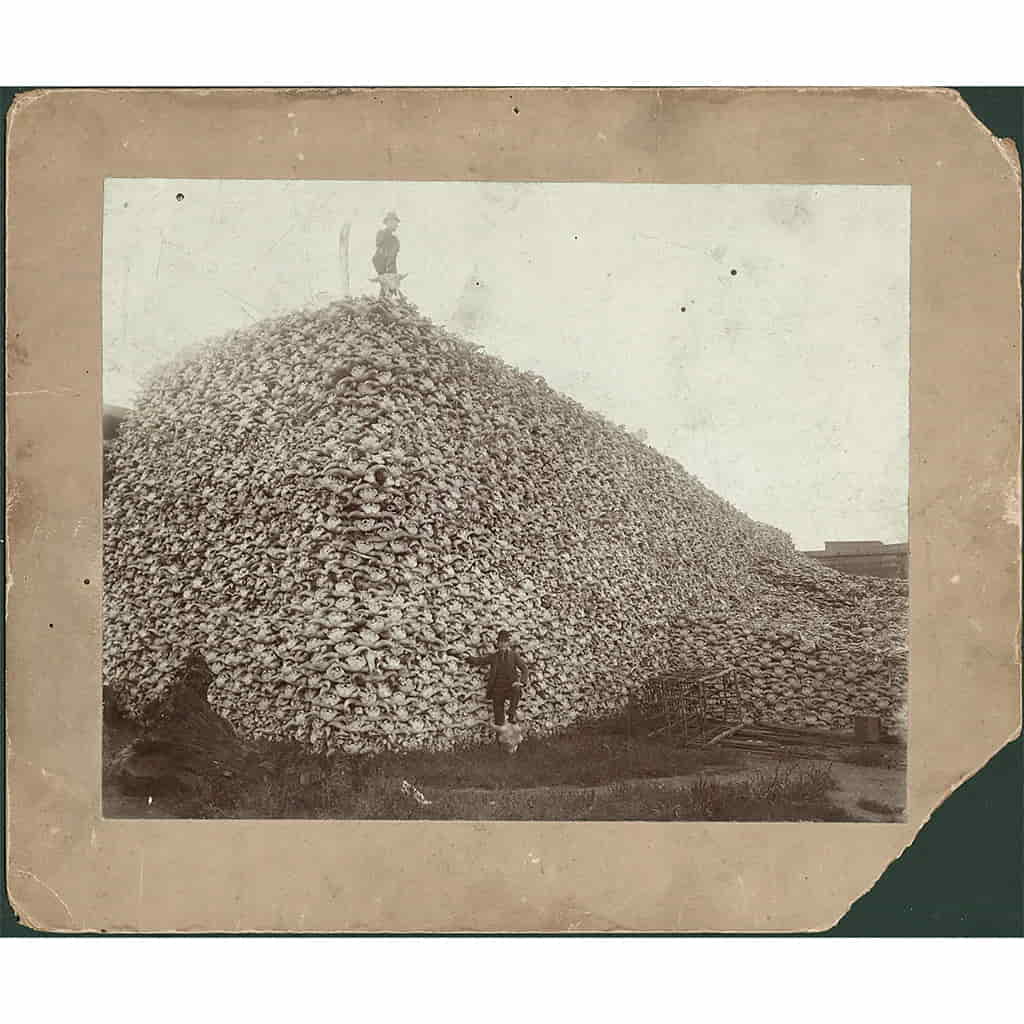

The famous image of two men posing on a mound of bison skulls is often seen as a symbol of the excessive hunting that took place during the colonization of the U.S. However, the story behind the photo reveals a much darker, calculated campaign aimed at eradicating the bison population, depriving Native Americans of a vital resource, and forcing their relocation onto reservations under the control of white settlers.

In the photo, two men dressed in black suits and bowler hats stand proudly beside a towering pile of bison skulls. The skulls, neatly arranged in rows, represent the result of years of excessive hunting. But, according to experts, this wasn’t just about overhunting—it was a deliberate strategy to undermine Indigenous nations and control their way of life.

Tasha Hubbard, a Cree filmmaker and professor at the University of Alberta, describes the bison’s mass slaughter as a “strategic” effort in the colonization process. The destruction of the bison, she explains, was seen as a way to “tame” the American West, enabling the expansion of white settlement. For the Native American tribes who relied on bison for food, clothing, and tools, the loss of the bison was devastating. It was a calculated effort to starve and weaken these communities, making it easier to control and relocate them.

A Devastating Loss for Native Americans

Native Americans had relied on bison for centuries. The animals were central to their nomadic cultures, providing essential resources for food, shelter, and tools. But by the late 1800s, the bison population had drastically decreased. While Native Americans hunted fewer than 100,000 bison each year, the population of bison in North America once numbered between 30 and 60 million. By 1889, only 456 bison were left in the U.S., many of which were in captivity and protected in places like Yellowstone National Park.

This photo isn’t just a historical reminder of colonial exploitation—it also reflects the broader issue of modern consumer practices. Bethany Hughes, a professor at the University of Michigan and member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, argues that the mass slaughter of bison was intertwined with the desire for land, wealth, and power. The economic boom driven by bison products like hides and bones was built on the backs of Indigenous peoples, whose land, culture, and autonomy were stripped away in the process.

The Economic and Military Drivers of Bison Extermination

The bison massacre was driven by multiple factors, including the building of railroads that opened new markets for bison hides, the advent of modern rifles that made hunting easier, and a lack of regulation. But the destruction of the bison was also part of a broader military strategy. Officials, like General Phillip Sheridan, recognized that eliminating the bison would severely impact Native American tribes, forcing them to abandon their nomadic ways and settle on reservations.

Sheridan famously advocated for the bison’s extermination as a tactic to subdue Native American tribes. He argued that “destroying the Indians’ commissary”—the bison—would make them easier to control. His words reflected a broader military and political effort to weaken and displace Indigenous peoples. For Native Americans, the bison’s loss was not just a matter of economics; it was a matter of survival and cultural identity.

The Legacy of Bison Extinction and Its Modern Implications

The loss of the bison had long-lasting effects on Native American communities. The forced relocation and deprivation that followed the bison’s near-extermination caused immense physical and psychological harm to these tribes. As noted by historians, tribes that relied heavily on bison experienced higher rates of child mortality, lower income, and poorer health compared to other Indigenous groups.

Despite the catastrophic decline, there has been some progress in recent years to restore the bison population. Conservation efforts, such as the U.S. government’s pledge to restore bison through the Inflation Reduction Act and smaller restoration projects by groups like The Nature Conservancy, are working to bring the bison back to their native lands. But the bison population has yet to fully recover, and the species remains near-threatened.

A Powerful Message for Today

Bethany Hughes argues that the photo of bison skulls represents more than just a historical atrocity—it highlights the ongoing issues of colonialism, capitalism, and environmental destruction. The image serves as a stark reminder of the ways consumer demand can drive colonial projects that exploit natural resources and harm Indigenous peoples.

As Hughes points out, when we objectify nature or dehumanize others, we lose sight of our relationship with the world around us. The photo of the bison skulls is not just a reminder of the past, but a call to examine how these systems still impact our environment and society today. It reminds us that the destruction of the bison was not only about killing animals—it was about killing cultures, economies, and communities.

This photo, while a symbol of past oppression, carries a message that challenges us to reflect on the continued exploitation of natural resources and the legacies of colonialism. It forces us to confront the ongoing ways in which we, as consumers, are part of the systems that perpetuate harm to both people and the planet.

Source

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.