The Most Controversial Chess Match of All Time: Kasparov, Karpov, and the KGB?

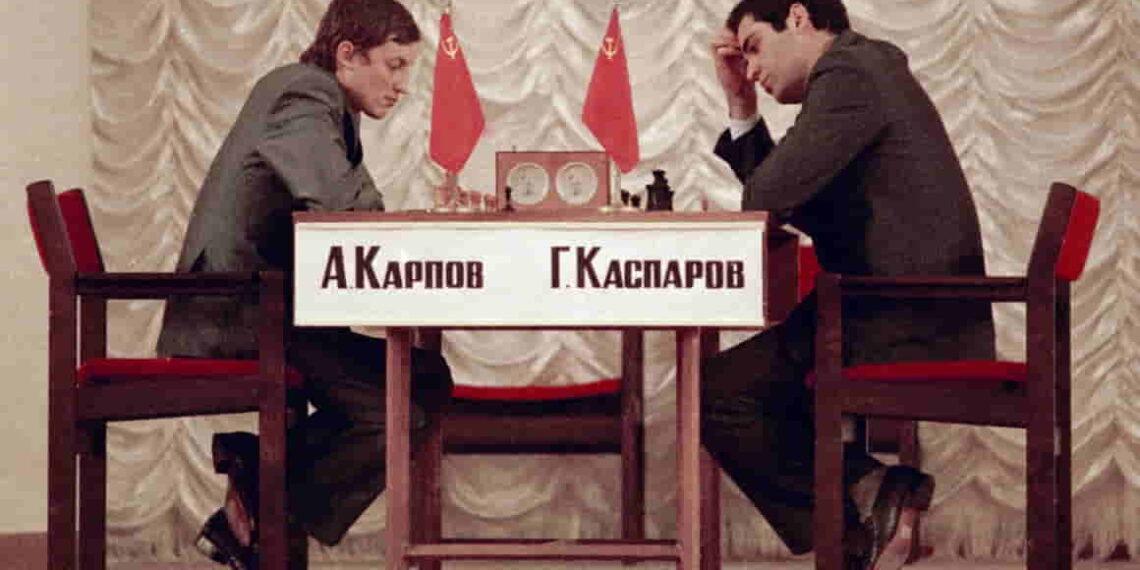

Forty years ago, the world witnessed the most controversial chess match in history—the 1984-85 World Chess Championship between Garry Kasparov and Anatoly Karpov. What was meant to be a battle of intellect and strategy became a symbol of political struggle and Soviet power.

The match lasted five grueling months, the longest in championship history, before being abruptly halted without a winner. To this day, questions linger: Was it really about player exhaustion, or were there hidden forces at play?

A Shocking Announcement

For Russian-born chess grandmaster and émigré Gennadi “Genna” Sosonko, the moment the match was abandoned remains vivid.

“I couldn’t come to the Soviet Union, of course. I was an enemy as far as they were concerned,” he told CNN Sport. “I remember that day very well because I was in Switzerland with Viktor Korchnoi, helping him prepare for one of his own matches. We were listening to the Swiss radio, analyzing, when we heard that (FIDE President Florencio) Campomanes stopped the match.

‘Well, well, well, how is this possible?’”

The match had become more than just a game. It had taken on symbolic meaning:

- If Karpov won, it would affirm the dominance of the Soviet establishment.

- If Kasparov won, it would signal change—something new, fresh, and perhaps threatening.

Instead, after 48 games, no winner was declared. But why?

Chess in the Soviet Union: More Than Just a Game

In the Soviet Union, chess was not just a pastime—it was a national obsession.

“It was more than just a sport,” Sosonko explains. “Chess in Russia was a kind of religion.”

The dominance of Soviet players in the chess world was unparalleled. From 1948 to the end of the 20th century, FIDE organized 23 World Chess Championships. Only one, the 1972 match won by American Bobby Fischer, was not claimed by a Soviet or former-Soviet citizen.

Under Soviet leaders like Khrushchev, Brezhnev, and Andropov, chess was used as propaganda, much like hockey and soccer. Elite players were treated like royalty.

“The conditions for Soviet players were incomparable to those in the West,” Sosonko recalls. “They had carte blanche at restaurants, luxury hotels, and earned unbelievable fees in hard currency.”

At the heart of this system was Anatoly Karpov.

Karpov: The Soviet Champion

By 1984, Karpov had been world champion for a decade. He was more than just a chess player—he was a national symbol.

“He was a Russian from the Ural region and represented the Soviet Union with glamor,” Sosonko explains. “He was a god in Russia.”

As one of the few Soviet citizens allowed to play abroad and collect foreign prize money, Karpov was also among the wealthiest people in the country.

“He was one of only three or four people in the Soviet Union who had a Mercedes. One was Brezhnev, another was (singer) Vladimir Vysotsky, and the third was Karpov,” Sosonko says.

His privileges were unimaginable to the average Soviet citizen.

Kasparov: The Outsider

If Karpov was the embodiment of the Soviet establishment, Kasparov was its challenger.

“He had a couple of weaknesses in the eyes of the big Party guys,” Sosonko notes. “Namely, he was not Russian—he was half-Jewish and half-Armenian, from Baku. And the Soviet Union was very antisemitic.”

Unlike Karpov, who was closely tied to the Communist Party, Kasparov represented something different.

“He wasn’t a dissident, but he was young, ambitious, and connected with people who weren’t for the regime,” Sosonko says.

Even in their playing styles, the contrast was clear:

- Karpov played conservatively, slowly building up his position.

- Kasparov was aggressive, dynamic, and preferred quick victories.

“No one was indifferent,” says American grandmaster Andrew Soltis. “You were either a Karpov fan or a Kasparov fan—there was no middle ground.”

A Marathon Match Turns Controversial

The championship followed the old rules: The first to win six games would be crowned champion, with draws not counting toward the total.

Early Domination by Karpov

- After nine games and 25 days, Karpov led 4-0.

- The next 17 games ended in draws, keeping the score stagnant.

- Karpov finally won game 27, pushing his lead to 5-0—just one win away from defending his title.

Kasparov’s Comeback

But Karpov was faltering. Mistakes crept into his game. In game 32, Kasparov finally won his first match.

- Another 14 games were drawn.

- In games 47 and 48, Kasparov won two more times, bringing the score to 5-3.

Karpov, once dominant, was now struggling.

The Match Is Stopped

After 48 exhausting games, FIDE President Florencio Campomanes made a shocking announcement: The match was being abandoned.

The official reason? Player exhaustion—particularly Karpov’s deteriorating health.

- He had lost 22 pounds over the course of the match.

- He struggled to sleep, staying awake later and later as the match dragged on.

But many questioned whether this was the real reason.

A Hidden Agenda?

Campomanes’ decision to halt the match has been debated ever since.

Was FIDE Under Soviet Influence?

“FIDE was completely under the influence of the Soviet Union,” Sosonko claims. “We knew that Campomanes was on their side.”

Though current FIDE CEO Emil Sutovsky disputes this, there were undeniable Soviet ties.

A KGB Connection?

Some even speculated that Campomanes was a KGB agent.

While Sosonko dismisses this as an oversimplification, he acknowledges:

- “He was on the Soviet side in all aspects.”

- “There was this invisible hand benefiting Karpov.”

Deliberate Delays

Soltis points to mysterious postponements as evidence of bias.

“Normally, players could only delay a game for medical reasons,” he explains. “But there were unexplained delays ordered by officials. These always seemed to benefit Karpov.”

Campomanes’ reputation shifted during the match. Initially seen as independent, he was later viewed as working in favor of the Soviets.

The Aftermath: Kasparov’s Legacy

While the 1984-85 championship ended without a winner, history had the final say.

- Later that year, Kasparov defeated Karpov in a rematch to become the youngest world champion in history.

- He then beat Karpov again in the next three World Championship matches.

Today, he is regarded as one of the greatest chess players of all time.

Politics and Chess: Then and Now

The Soviet Union may be gone, but Russia’s use of sports as political propaganda remains.

Soltis notes, “Russia is still trying to use sports, including chess, as a political weapon. A leopard doesn’t change its spots.”

With tensions high in today’s geopolitical climate, the echoes of the 1984-85 championship still resonate. It was more than just a chess match—it was a battle for the future.

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.