80 Years After WWII, Okinawa’s Battle Sites Still Reveal Bones and Bombs

Eighty years after the Battle of Okinawa, remnants of one of the fiercest and most deadly conflicts in the Pacific continue to surface, from human bones to unexploded bombs. Amidst the lush jungle of Okinawa’s hills, a “bone digger” named Takamatsu Gushiken spends his time excavating caves where civilians and soldiers sought refuge during the battle. His mission is to uncover the lost remains of those who perished in the conflict, offering a sense of closure to the decades-old scars of war.

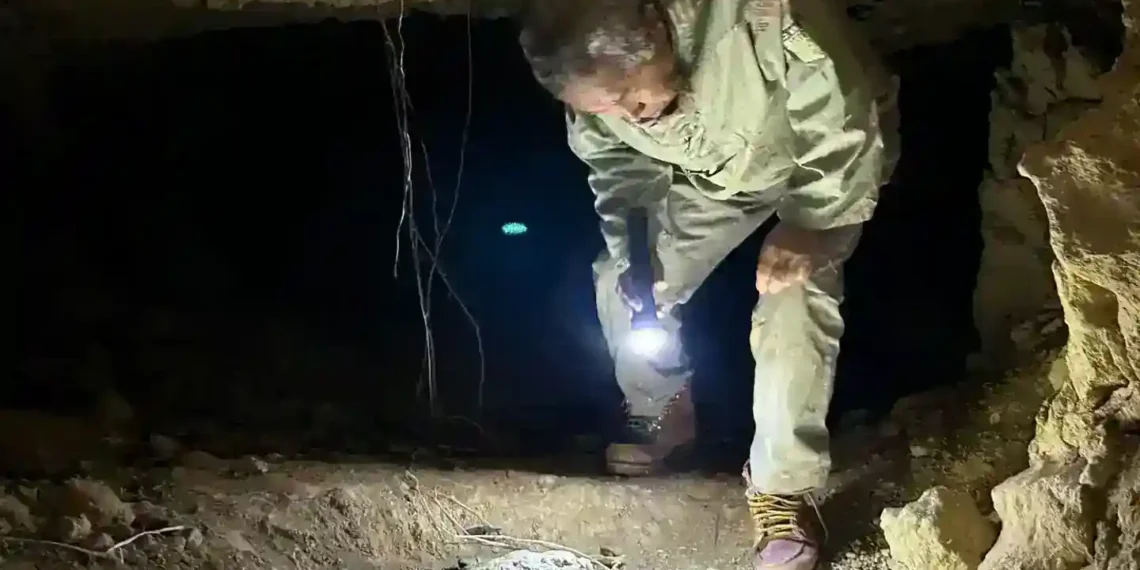

Gushiken moves with precision through a narrow crevice in the cave, his flashlight illuminating bits of bones—a skull fragment, some smaller bones, possibly from a child. He speaks softly, his voice breaking with emotion, explaining why he’s drawn to this work: “They are human, and I am human too.” His discoveries paint a haunting picture of the past: a mother and child, trapped in a cave as US forces attempted to clear out hidden defenders, caught in the crossfire of war.

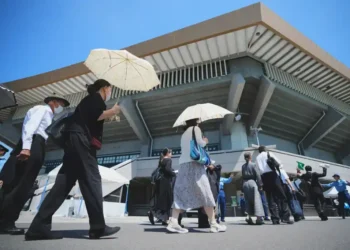

The Battle of Okinawa, fought between April and June 1945, claimed the lives of over 240,000 people—roughly 100,000 civilians, 110,000 Japanese soldiers and conscripts, and more than 12,000 American and allied troops. The battle’s brutal nature is evident in the overwhelming firepower used by American forces, including over 16 million machine gun rounds and 9 million rifle bullets. The legacy of that destruction is still felt today, as bones and remnants of the war continue to be uncovered on the island.

The island’s battle-scarred landscape offers visitors a rare opportunity to connect with history. On Ie Shima, the shell of a pawn shop is the only building to have survived the battle. At Tomigusuku, remnants of the Japanese Navy’s underground headquarters, where Vice Admiral Minoru Ota and 4,000 of his men took their own lives, stand as silent witnesses to the horrors of war. Nearby, caves with unexploded grenades and machine gun emplacements serve as eerie reminders of the conflict’s brutal nature.

For those eager to understand the full extent of the battle, the Okinawa Prefectural Archives offers a unique experience. Through archival photographs, visitors can compare the island’s current landscape with images from the battle, bringing the devastation of 1945 into sharp focus. Kazuhiko Nakamoto, an archivist and descendant of a survivor, reflects on the war’s impact on his own family, explaining how his mother, a young girl during the battle, miraculously survived amidst the chaos.

The archives also offer a poignant look at how Okinawans were caught in the crossfire of a war that was not of their making. Many Okinawans initially thought the Japanese troops were there to protect them, only to find themselves enlisted in a war they couldn’t escape. Textbooks promoted militarism in schools, preparing students—often young girls like the members of the Himeyuri Student Corps—to serve in the war effort.

The Himeyuri Peace Museum brings the stories of these young girls to life. Teenage students from Okinawa’s women’s schools were pressed into service to nurse injured soldiers in caves during the battle. Many of them witnessed the horrors of war firsthand, performing amputations without anesthesia, caring for soldiers delirious from brain fever, and burying their fellow students killed by gunfire.

The museum’s video testimonies, told by surviving students, are raw and heartbreaking, offering an intimate glimpse into their unimaginable suffering. The museum honors the 227 girls who died or went missing, many whose fates remain unknown. These haunting stories often evoke thoughts of the bones Gushiken finds in the caves—could they belong to one of these young girls?

Though only a small fraction of the remains found have been identified, Gushiken is committed to his work. However, he hopes for more action from the authorities, asking for improved technology to help identify the remains and return them to their families. “I hope the authorities will take a more proactive approach to identifying the bones,” he says.

On the American side, Steph Pawelski, a US Department of Defense teacher and military spouse, is similarly dedicated to preserving the history of Okinawa’s battle sites. Her interest in the battle’s history is personal—both of her grandfathers served on the island. Using old photographs, Pawelski retraces their steps, connecting the past with the present.

Pawelski’s work also extends to supporting veterans, like Neal McCallum, a Marine who fought on Okinawa and was wounded during the battle. McCallum, now 98, plans to return to Okinawa for the 80th anniversary of the battle, seeking closure for the events of 1945. Pawelski helps him navigate the island, ensuring that he visits the sites that hold the most significance for him.

McCallum’s reflections on his journey reveal how his perspective on the war has evolved. He recalls how, in 1981, a chance encounter with Japanese schoolchildren changed his deep-seated hatred of the Japanese. “I thought, what a fool I am for hating them,” he says, emphasizing the importance of forgiveness and understanding.

As Gushiken continues his work in the caves of Okinawa, he reflects on the lessons of the past. “No more wars,” he says. His hope is that by uncovering these remains and bringing attention to the horrors of war, future generations will be reminded of the importance of peace. In the end, the bones and battle sites are not just relics of history—they are a call for humanity to never forget the cost of war and to strive for a world free of violence and conflict.

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.