LOS FARALLONES DE CALI, Colombia — The park ranger trudged through the red mud, beneath the fog-covered Andean mountains he was tasked with protecting, on a path leading to the biggest threat facing this forest.

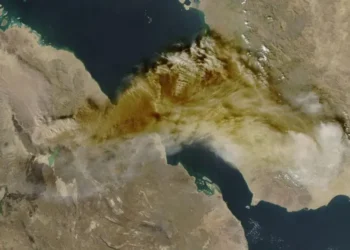

About four miles up the mountain from a broken sign that reads “You are inside a protected area,” miners had ripped into the soil in one of the most biodiverse regions of Colombia in search of gold, spilling poisonous mercury used in the extraction process into rivers that nourish this forest.

Colombia has pledged to close the illegal gold mines threatening this park, home to hundreds of species of birds, rare poisonous frogs and the nation’s emblematic Andean bears.

But Jaime Millán, one of only 13 permanent staff members overseeing a national park stretching across more than 480,000 acres and four ecosystems, knows it won’t be easy. “You have to understand the essence of the miner,” Millán said. “Where there’s gold, he’ll go.”

The lack of resources to protect wilderness in some of the most biodiverse places on Earth is at the heart of a major international conference starting Monday, just an hour away from the park.

Leaders from around the world are gathering in Cali for the next two weeks for a U.N. biodiversity summit, called COP16, where Colombia and other species-rich nations will urge wealthy ones to make good on financial commitments to protect natural habitats.

The world is in the midst of a global extinction crisis, with up to a million species at risk of disappearing forever due to shrinking habitats, rising temperatures and other threats posed by humans.

Around the world, ecosystems like this one are deteriorating, with potentially calamitous effects for people who depend on nature for food, water and keeping climate-warming carbon out of the atmosphere. Yet many of the world’s most ecologically rich countries — in South America, Africa and Southeast Asia — are often among the poorest financially.

“Today, those who emit the most are the ones who have the cheapest access to capital and those of us who are absorbing and mitigating those greenhouse gases are offering environmental services that are not recognized whatsoever,” said Susana Muhamad, Colombia’s environment minister.

‘A transfer back’

The conference near this park is a follow-up to a watershed agreement reached two years ago to stem the loss of nature worldwide. Nearly 200 nations promised to safeguard about a third of Earth’s land and oceans.

The deal, forged in talks in Montreal, “was a game changer for biodiversity,” said Astrid Schomaker, executive secretary of the Convention on Biological Diversity, the treaty underpinning the talks.

The conference in Colombia represents the first time nations are officially coming together to assess how close they are to reaching those goals, including voluntary pledges by wealthier nations to support conservation in poorer ones.

“This is the first temperature check of, ‘So what are people doing on this?’” said Charles Barber, a former U.S. State Department diplomat who is now a director at the World Resources Institute.

Early data suggests countries need to give more to meet those money pledges.

Out of a goal of mobilizing $200 billion a year for conservation, developed countries promised to send at least $20 billion per year by 2025. Much of the rest will come in the form of funds that governments spend within their own borders.

Historically, many nations built wealth by extracting resources from poorer ones, noted David Obura, a coral reef ecologist in Kenya who chairs the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, a U.N.-backed science group. “It’s a bit of a transfer back,” he said.

Yet so far, wealthy nations are ponying up only three-fourths of that annual amount, according to a recent report.

“They wrote a check in Montreal that they can’t cover, basically,” Barber said, adding that governments seek to make sure money sent abroad is being spent correctly. “That involves efforts to reduce corruption,” he added.

With territory encompassing huge swaths of the Amazon rainforest and coastlines stretching along both the Atlantic and Pacific, Colombia is one of the most biodiverse places on Earth. Yet the challenge of protecting a place like Farallones de Cali national park is complex and costly: A decades-long armed conflict, rooted in disputes over land, makes the job especially dangerous for park rangers like Millán.

The country’s protected national parks, often in isolated mountainous or jungle regions, have been used as strategic staging points for armed groups to grow coca, used to make cocaine, and set up hideouts for the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC, a rebel group.

National parks staff were often caught in the middle, threatened or even killed by these armed groups, according to Colombia’s peace jurisdiction. Millán himself has been threatened, after a group of miners saw him flying a drone over the area.

Authorities have stationed soldiers along the trail to the mines and are building control towers to keep watch. But Millán has many things he still needs: more staff, satellite radios and walkie talkies to communicate; better trekking gear to lead hikes.

Catalina Gutiérrez Chacón, the Colombia director for the Wildlife Conservation Society, said the national parks system needs at least five times more funding than it receives, suggesting it needs a new structure to ensure more funds reach the park staff level to hire more permanent staff like Millán.

Local rangers

Right now, the world is falling short of the Montreal agreement’s biggest goal: Protecting 30 percent of Earth as wilderness.

As of August, only about 17.5 percent of Earth’s land and freshwaters and 8.5 percent of its oceans are safeguarded, according to a U.N. monitoring program. And as of Sunday evening, only 33 nations have provided updates on how they plan to protect nature ahead of the meeting in Cali, though Schomaker expected more plans to be put forward during the conference.

“That’s pretty slow, so we need to see acceleration of that,” said Andrew Deutz, a director at the World Wildlife Fund.

In addition to money, delegates at the COP will also be discussing how to ensure the people who live in these biodiversity havens thrive.

The situation in Colombia shows how fraught that question can be. Heading into Los Farallones, Millán points out one of the park’s greatest challenges: A more than 80-year-old paved road that existed long before the area was declared a protected national park in 1968.

Slicing through the national park, it has long made it accessible to land and gold prospectors. Generations of families built their lives in communities abutting the forest.

Large stretches of farmland, deforested long ago, create gaps in the otherwise lush mountain landscape and reveal the inherent tensions between the park’s environmentalists and its residents, who depend on the land for their livelihoods.

Now, some of those residents are becoming stewards of these wild places.

A brief drive on a dirt road, across a creek, leads to the home of 80-year-old Hernando Bolaños, whose father settled here when the land was considered vacant.

At one point, the Bolaños family raised more than 50 cows on their dairy farm. Now they own about half that number and have signed an agreement with the national park to restore the forest on their land. More than three years ago, Bolaños’s son, José, started separating the cows from a creek and fenced off an area to plant new trees. The area is now lush with vegetation.

He is now one of about 80 contractors working with the national park. But while José Bolaños works for the park, he never wears the uniform. Cutting through his land are the two main paths to reach the illegal gold mines.

“When I’m walking up to the mine, I’m usually alone,” he said. “I’ve run into miners and it’s dangerous.”

Millán, the park ranger, hopes that by turning this area into a tourist destination where locals can take visitors hiking, birdwatching and horseback riding, and offer them food and even cabins in which to stay, perhaps it will help keep the miners away for good.

Long term, he would like to turn the mining route into a hiking route. But it would require setting up training, infrastructure, a marketing campaign — the kinds of investments the park has difficulty making and that foreign money could help fund.

“This needs to be appropriated by the people from the community,” Millán said.

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.