What Happened to the Funk?

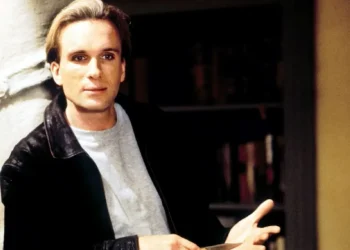

If there were a Mount Funkmore, Marcus Miller would be immortalized on it, his face forever carved alongside other legendary bassists, sporting his signature porkpie hat. For over 40 years, Miller’s electrifying bass lines have powered some of the most iconic funk grooves, inspiring listeners around the globe to “Get Up Off That Thing.” His work can be heard on tracks by Michael Jackson, Chaka Khan, and Luther Vandross. His live performance of Run for Cover is a prime example of what it means to play “in the pocket,” where the rhythm section locks into a groove so tight that it forces the musicians to smile and nod at one another in musical bliss.

Miller’s musical journey began during funk’s golden era in the ’70s. It was a time when tracks from bands like Ohio Players and Parliament blasted from dorm rooms and basement parties, marking the rise of funk as “the chocolate-colored soundtrack to a golden age of music,” as cultural critic Michael A. Gonzales once described. Miller, now 65, puts it simply: “There’s no sad funk songs. Funk’s primary purpose is to get people moving, dancing, and shaking their behinds.”

Fast forward to 2025, and it seems that funk has lost its groove in the face of global challenges—plunging stock markets, rising prices, job layoffs, and political polarization. While these issues dominate the news, one lingering question is: What happened to the funk?

I grew up in the heart of funk’s golden era, just as so many others did. I watched Earth, Wind & Fire live, caught the latest dance moves on Soul Train, and embraced the defiant attitude that funk embodied—wearing an Afro pick with a clenched Black fist handle. Funk wasn’t just music; it was a lifestyle, a collective experience that brought people together through music, dance, and a shared sense of joy.

But somewhere along the way, something changed. In the ’80s and ’90s, the rise of hip hop, rap, grunge, and alternative rock shifted the musical landscape. Today, pop charts are dominated by synthetic dance hits that sound like they’ve been churned out by an AI bot. So, why did funk fade from the limelight, and what did we lose along the way?

A recent documentary, We Want the Funk!, directed by Emmy-award-winning filmmakers Stanley Nelson and Nicole London, explores this very question. It takes audiences on a journey to the roots of funk music, featuring legends like George Clinton and Marcus Miller, along with members of funk powerhouses like the Ohio Players.

The film highlights how funk music was born in the heart of James Brown. The Godfather of Soul pioneered the genre in the ’60s with hits like I Got You (I Feel Good) and Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag. Brown’s sound was stripped-down yet dynamic, defined by syncopated drums, driving bass lines, and blazing horns. His funky presence, Clinton says in the documentary, was undeniable. “Even if he sang the Star-Spangled Banner, it was going to be funky.”

Though funk began with individual performers, its true power came from community. Funk’s biggest acts were ensembles, and bands like Lakeside and Sly & the Family Stone exemplified a sense of unity. Marcus Miller, who grew up in Queens, New York, recalls how every block seemed to have its own funk band. Making a band click required constant rehearsals and arguments, but when it came together, the result was pure magic—much like a championship basketball team, Miller says. “Everybody plays the hell out of their role.”

This communal energy was felt deeply by audiences. Watching vintage performances, it’s clear that funk music had the power to bring people together, creating a sense of collective joy that was as powerful as anything I experienced in church. Funk wasn’t about “I”; it was about “we.” As Sly and the Family Stone sang, “Everybody take it to the top, we’re gonna’ stomp all night.”

Funk was also revolutionary in its inclusivity, bringing together musicians of all races. The genre’s interracial bands, like Sly & the Family Stone, offered a vision of racial harmony that was rare in America. “Sly & the Family Stone was the musical equivalent of ‘I Have a Dream,’” says drummer and producer Questlove in the film.

For me, growing up in a segregated Black community, seeing Black and White musicians working together in harmony was a radical act of optimism. Funk music transcended racial divisions, allowing us to dream of a world where differences could be set aside and unity could thrive.

There were moments when funk bands challenged expectations. The release of Bobby Caldwell’s What You Won’t Do For Love in 1978 stunned audiences when they realized the soulful voice behind the track belonged to a White man. Similarly, the Average White Band’s Pick Up the Pieces and Wild Cherry’s Play That Funky Music proved that funk wasn’t confined to any one race—it was a universal language.

So, what killed the funk? Some point to the rise of hip hop and rap, while others believe the business side of music is to blame. In the 1980s, record companies began to prioritize solo artists, seeing them as more profitable than large bands. Technology, too, has played a role, allowing solo artists to create hits from their bedrooms. “A solo artist can record a song at their house on their laptop and become a massive hit,” says Miller, who has shifted his focus to composing for film and TV.

Funk’s communal spirit has been replaced by a more isolated, “I” society. As sociologist Robert D. Putnam notes, we’ve become loners rather than joiners, leading to a decline in live band culture. Instead of gathering to dance and share the groove, we increasingly turn to screens, tuning out the collective experience that once made funk so powerful.

Despite its fading presence in mainstream music, funk’s influence endures. Elements of the genre still show up in hip hop, contemporary jazz, and even marching bands. Uptown Funk by Mark Ronson and Bruno Mars proves that the funk isn’t dead—it’s just been reimagined for a new generation.

And while today’s pop music may seem shallow compared to funk’s deep grooves, the spirit of the music lives on. Funk bands no longer dominate the airwaves, but cover bands across the globe—many in places as far-flung as Russia and Australia—keep funk alive. Funk dance routines, like those by Japanese choreographer Moga, show that the genre still has a global appeal.

Funk may have faded from the spotlight, but its legacy continues. It’s the music of togetherness, the rhythm that unites us. It’s a reminder that no matter who we are, where we come from, or what we believe, we all need the funk. And thankfully, it’s a groove we can’t quite let go of.

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.