‘A Huge Loss’: Japan’s Hidden Christians Face the End of a Unique Faith Tradition

IKITSUKI, Japan — On a quiet, remote island in Nagasaki Prefecture, a small group of believers gathers to worship in a way few outside their community understand. They are Japan’s Hidden Christians, guardians of a rare, centuries-old faith tradition they call the “Closet God.”

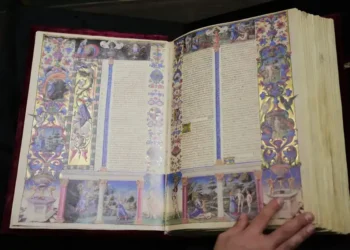

In a modest room no larger than a tatami mat, they venerate scroll paintings that don’t look like typical Christian icons. One shows a kimono-clad woman resembling a Buddhist Bodhisattva holding a child — to outsiders, a Buddhist image, but for them, a secret symbol of Mary and baby Jesus. Another scroll depicts a man wearing a camellia-covered kimono, alluding to John the Baptist’s martyrdom. There’s even a ceramic bottle of holy water from Nakaenoshima, where Hidden Christians were brutally persecuted in the 1620s.

The catch? None of these symbols scream “Christianity.” That’s precisely why they exist — they were disguised to survive over 250 years of deadly persecution by Japan’s isolationist rulers.

A Hidden Faith Born of Persecution and Persistence

Christianity arrived in 16th-century Japan with Jesuit missionaries who quickly won converts, especially in Kyushu, the southern island where Nagasaki’s trading ports flourished. By some estimates, hundreds of thousands embraced the new faith.

But the shoguns soon saw Christianity as a threat. From 1614, brutal crackdowns forced believers underground. Foreign missionaries were expelled, and thousands of Christians were killed.

For more than two centuries, these Kakure Kirishitan — or Hidden Christians — secretly nurtured their faith, adapting it to survive. They disguised Christian symbols as Buddhist or Shinto icons and created rituals blending old prayers with new meanings.

When the ban lifted in 1865, some returned openly to Catholicism. But many continued practicing their secret version, handed down through generations.

Living Relics of a Vanished Japan

Today on Ikitsuki and nearby islands, Hidden Christians still worship in their ancient way. They chant in archaic Latin mixed with Japanese, a language almost lost outside their community. Their prayers honor not only Jesus and Mary but also their ancestors — a reflection of how their faith interwove with local traditions.

Masatsugu Tanimoto, 68, one of the few remaining men who can still recite the Latin chants known as Orasho, says, “I’m afraid we’re the last. It’s sad to see this tradition end with our generation.”

The role of Oji — a local leader who presides over ceremonies like baptisms, funerals, and festivals — is passed around in the community. But these rituals, unchanged for centuries, happen less frequently as the population ages and young people leave for the cities.

A Faith Rooted in Ancestry and Adaptation

Hidden Christians’ survival depended on their ability to hide and adapt. They kept ritual objects secret, passed from household to household, and hid their faith within familiar Buddhist and Shinto customs.

Many refused to return to mainstream Catholicism after persecution ended. Catholic priests required rebaptism and the abandonment of Buddhist altars — a demand that felt like erasing their ancestors’ sacrifices and daily practices.

Tanimoto explains, “I’m not a Christian in the usual sense. Our prayers ask ancestors to protect us. We carry on what our ancestors believed, not just worship Jesus or Mary.”

The Fragile Future of Hidden Christianity

Once numbering around 30,000 in Nagasaki Prefecture during the 1940s, Hidden Christians now number fewer than 100 on Ikitsuki, according to estimates. The last recorded baptism was in 1994. Modern life has fractured the tight-knit farming communities that once sustained the faith.

Shigeo Nakazono, a local folklore expert who has studied Hidden Christians for decades, notes, “In today’s society, growing individualism and a lack of professional religious leaders make it hard to maintain this tradition.”

He has been working to preserve artifacts and record oral histories, trying to save a piece of Japan’s cultural heritage before it’s lost.

Holding On to a Legacy — But for How Long?

Masashi Funabara, 63, leads one of the last remaining Hidden Christian groups in his district. Once nine families strong, now only two remain. “Our ancestors kept the faith in fear of persecution for centuries. When I imagine their suffering, I feel we should not give up easily,” he says.

Funabara, like Tanimoto, hopes to pass the tradition to his children. “Hidden Christianity will likely go extinct eventually, but I want it to live on at least within my family — that’s my small hope.”

Why It Matters

For historians, religious scholars, and the communities themselves, the disappearance of Hidden Christianity is more than the loss of a faith tradition — it’s the fading of a living link to Japan’s tumultuous past, to stories of resilience, adaptation, and cultural blending that challenge our understanding of religion and identity.

As one expert said, “It will be a huge loss — not just for Japan, but for the world.”

If you want to learn more or support efforts to preserve this remarkable faith, many local museums and cultural groups welcome visitors eager to listen and understand these quiet guardians of history.

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.