For first-time visitors, stepping into a Turkish bath can feel like entering another world. The air is warm and dense with steam, sounds are softened, and light filters gently through small openings in the domed ceiling, casting shifting patterns across marble floors and walls.

In this hushed, humid environment, time seems to slow. The hamam is not simply a place to wash but a carefully designed space meant to calm the body and mind, shaped by centuries of tradition.

A Social Space With Deep Roots

Unlike private bathrooms or modern spas, the hamam has always been a communal setting. According to Ahmet İğdirligil, an architect and historian specializing in Turkish bath culture, this public nature is essential to understanding its role.

“In a bath or shower you are alone, but a hamam is a public space,” he explains. “It is a social place and historically a rare space where women could gather outside their homes without restriction.”

In Ottoman times, women from affluent families often visited the hamam regularly, and some even had private baths built into their homes. Visits were marked by personal belongings: ornate hamam tası bowls for pouring water, embroidered cloths edged with lace, and finely woven peştemal towels, traditionally made of cotton with hand-finished edges to prevent fraying.

Beyond daily hygiene, hamams were closely tied to social and religious customs. Over generations, detailed rules evolved around cleanliness for specific life events, including marriage, childbirth, menstruation, and religious observance. In smaller towns today, women still visit hamams not only for relaxation but also to socialize, step away from domestic responsibilities, or even seek potential brides for their sons.

Architecture Designed as a Journey

A traditional hamam is structured to guide visitors through a gradual physical and sensory transition. İğdirligil notes that most hamams consist of at least three interconnected sections, each with a distinct temperature and function.

The first area is the entrance and changing room, historically warmed by a soba, or wood-burning stove. This space includes lockers and a lounge where guests rest after bathing. From there, a door leads to a semi-warm room with toilets, depilatory services, and kurna—marble basins used for rinsing.

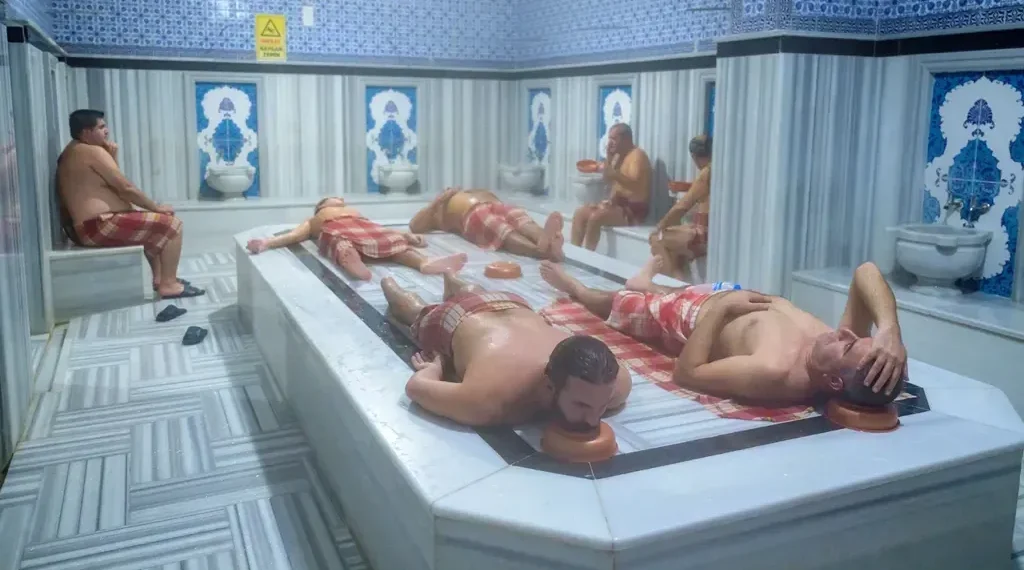

At the heart of the bath is the hottest and largest chamber, centered around the göbek taşı, a raised marble platform designed for sweating and treatments. Additional basins line the walls, and some hamams include smaller private hot rooms, known as halvet, branching off from the main space.

“The structure is very important because it is a journey into the hamam and back,” İğdirligil says. High domed ceilings, often taller than the room is wide, are punctured with small glass openings that resemble stars. These openings enhance both light and acoustics, giving the space a sense of openness and calm.

One of the best-known examples is Cağaloğlu Hamam in Istanbul, built in 1741 to help fund a library commissioned by Sultan Mahmut I. Its white marble interior and diffused light create an atmosphere that İğdirligil likens to floating. The combination of heat, humidity, and echoing sounds, he says, can feel womb-like and deeply soothing.

How a Hamam Visit Works

While the overall experience is similar across Turkey, individual hamams operate differently depending on size, age, and layout. Elif Kartal, guest relations and operations manager at Zeyrek Çinili Hamam, says most baths offer core services such as the kese body scrub and the köpük masaj, or foam massage, though details vary.

Of Istanbul’s 237 recorded hamams, only about 60 are still operating. Smaller baths often share facilities, with men and women bathing at separate times or on different days. Larger historic hamams, including Zeyrek Çinili and Ayasofya Hürrem Sultan Hamam, have fully separate sections for men and women. The latter, designed in 1556 by the Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan for Roxelana, the wife of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent, was the first to feature identical layouts for both genders.

Most hamams remain open until late evening, sometimes as late as 11 p.m., though advance booking is increasingly recommended.

Preparation and Practicalities

Experienced attendants advise guests to prepare carefully. Elif Tamtartar, a natır with 25 years of experience at Zeyrek Çinili Hamam, recommends avoiding waxing immediately before a visit and skipping body lotions or oil-based products the day prior.

“These reduce the effectiveness of the kese because the glove slides on the skin,” she explains. Eating lightly and avoiding alcohol are also advised, as the heat can be intense.

Hamams provide changing areas with lockers, and some ask guests to disclose basic health information. Disposable underwear is usually offered, though guests may bring their own or wear swimwear. Because the scrub covers most of the body, one-piece swimsuits are generally discouraged.

The Ritual of Cleansing

Once changed and wrapped in a peştemal, guests are guided by a natır, or for men, a tellak, into the warm inner chambers. At Zeyrek Çinili Hamam, attendants lead guests by hand through the semi-warm room into the central space, where warm water is poured over the body before resting on the heated göbek taşı.

After sweating, the attendant rinses the body using a bowl, carefully washing away accumulated heat and perspiration. Despite the name, there are no immersion baths in a hamam. İğdirligil explains that pre-Islamic Turkic beliefs regarded water as sacred, and pouring water rather than soaking preserved its purity.

The kese follows. Made from coarse fabric, the glove removes dead skin through firm, rhythmic strokes. Tamtartar says attendants are often called keseci among themselves, regardless of gender. The craft is typically learned through family tradition rather than formal training.

As the scrub progresses, thin layers of dead skin roll away, followed by a gentler cleansing with lif, or loofah, made from materials such as cotton or goat hair.

A Timeless Sense of Renewal

The ritual concludes with the köpük masaj. Using olive oil-based soap, attendants create billowing foam with a muslin cloth before massaging it across the body. Olive oil soap, long favored in Turkey, cleans without stripping natural oils, leaving skin noticeably soft.

After a final rinse and hair wash, guests return gradually through the cooler rooms, where they are dried, wrapped in towels, and encouraged to rest with tea. Leaving too quickly is discouraged, as the body needs time to adjust.

For many, the hamam experience goes beyond physical cleanliness. “Guests forget their troubles,” Tamtartar says. “We approach them with a mother’s love. The energy of the water, the bath, and the person come together.”

Centuries after their origins, Turkish baths remain places of care, connection, and renewal—rituals shaped by history but still deeply relevant today.

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.