Inside Chile’s battle against the Tren de Aragua gang

July 28, 2025, 18:00 EDT

A quiet transformation is unfolding in northern Chile. In the border city of Arica, a team of prosecutors and investigators is dismantling one of Latin America’s most feared criminal organizations—Tren de Aragua—not through brute force, but through strategic prosecutions, digital forensics, and a deep understanding of transnational organized crime.

Their work is revealing the sophisticated inner workings of a gang that has spread across South America, fueled by Venezuela’s migration crisis and regional instability. As other governments crack down with mass deportations or militarized policing, Chile’s methodical approach is offering a rare success story.

Chile becomes a frontline in Latin America’s organized crime crisis

Once one of the region’s most peaceful nations, Chile has become a new battleground in the fight against organized crime. Tren de Aragua, a gang that originated in Venezuela, expanded into Chile around 2021, exploiting the flow of migrants and the country’s lack of experience with transnational mafias.

The gang quickly established roots in Arica’s shantytowns, notably in Cerro Chuño, an area that had once been a toxic waste site. Here, gang members extorted local businesses, engaged in human trafficking, and even constructed torture chambers.

Despite Chile’s reputation for low corruption and strong democratic institutions, it was unprepared for the surge in violence. Between 2019 and 2022, homicides in Arica rose by over 200%, according to local prosecutor Mario Carrera.

Detailed records reveal a criminal corporation, not just a street gang

Police raids on gang hideouts in Arica turned up a trove of documents—spreadsheets written in blue ink that meticulously recorded every financial transaction. These included small expenses like $9 for coffee and $15 for rides, but also detailed salary structures, earnings from sex trafficking, and bonuses for hitmen.

These records, obtained and reviewed by The Associated Press, offered unprecedented insight into Tren de Aragua’s structure. According to prosecutor Bruno Hernández and his team, the gang operated like a multinational company, with a clear hierarchy and decentralized branches that still adhered to central leadership principles.

“We had to prove not only that they committed crimes,” said legal assistant Esperanza Amor, “but that there was a structure and pattern. Otherwise, they would’ve been treated like common criminals.”

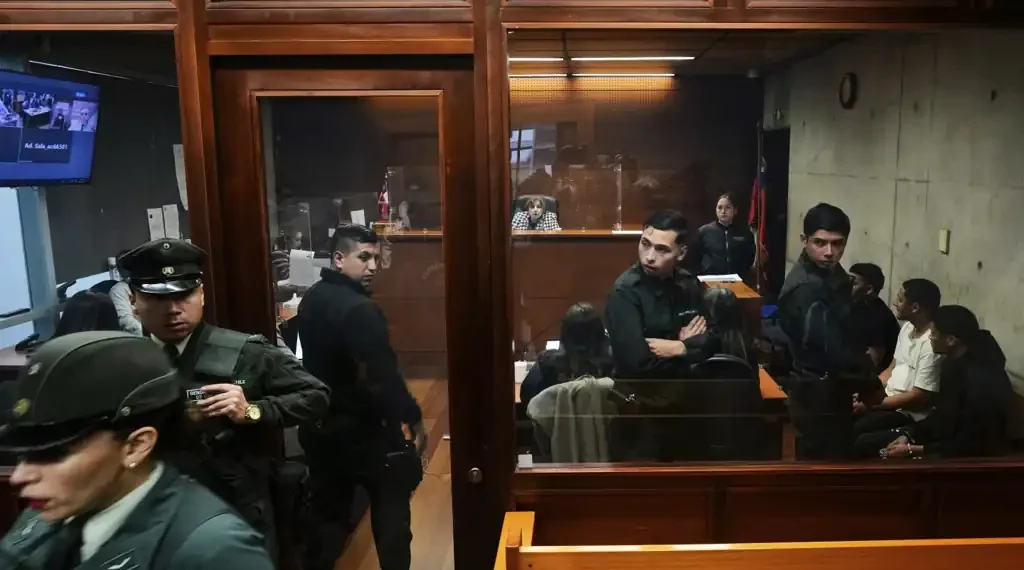

A legal breakthrough: Chile’s first major convictions against the gang

In March 2024, after years of investigative work, Chilean prosecutors achieved a legal milestone. Thirty-four gang members were convicted in Arica on charges including aggravated homicide, human trafficking, and sexual exploitation of minors. Earlier this month, a dozen more leaders were sentenced to a combined 300 years in prison.

The convictions came without cooperation from most of the accused. Prosecutors relied heavily on financial records and intercepted communications, sometimes decoded with the help of drone surveillance. They even deciphered the gang’s emoji-based code: a snake meant “traitor,” a pineapple indicated a safehouse, and a cloud warned of impending police raids.

As a result, Arica’s homicide rate fell sharply in 2023—from 17 to 9.9 homicides per 100,000 people, according to government statistics.

Migrants, violence, and a network that spans continents

Tren de Aragua’s rise across South America coincided with the collapse of Venezuela’s economy. As millions fled, some fell prey to smugglers and criminal networks. The gang exploited these migration flows to expand into Colombia, Peru, and eventually Chile.

Héctor Guerrero Flores, also known as “Niño Guerrero,” is believed to have directed operations from Venezuela. His lieutenants took over human smuggling routes and set up operations in cities like Arica, where desperate migrants live in vulnerable conditions.

In Chile, the gang’s main revenue sources included smuggling, sex trafficking, and extortion. Court documents described gruesome tactics: dismemberment of enemies, torture of defectors, and routine threats made by phone from inside prisons.

A global contrast: Deportation versus prosecution

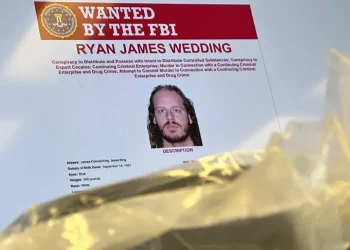

While Chile’s slow, methodical legal strategy shows promise, other countries have chosen different paths. In the United States, the Trump administration designated Tren de Aragua as a terrorist group and used its presence to justify increased deportations.

Some experts argue that approach misses the bigger picture.

“With the U.S. snatching guys off the streets, they’re taking out the tip of the iceberg,” said Daniel Brunner, a former FBI agent and president of Brunner Sierra Group, a security consultancy. “They’re not looking at how the group operates.”

Brunner and others warn that without investigations and international cooperation, criminal networks adapt and continue to function, often from within detention centers.

A city still haunted—and a country still debating

Despite progress in courtrooms, the gang’s influence hasn’t vanished. Prosecutor Hernández said some extortion calls still come from prison phones. The challenge now is monitoring how Tren de Aragua’s jailed members may regroup.

“Organized crime will always adapt,” Hernández noted. “We need to stay ahead.”

Public anxiety remains high. National homicide rates are down, but fear persists. Many Chileans now support more hardline policies—mirroring what’s been seen in El Salvador under President Nayib Bukele.

Far-right presidential candidate José Antonio Kast, currently leading in the polls, has vowed to deport undocumented migrants and build a border barrier. His rhetoric echoes Donald Trump’s policies and resonates with older Chileans like 70-year-old Maria Peña Gonzalez.

“You can’t walk at night like you could before,” she said from outside a church in Arica. “Chile has changed since different types of people started arriving.”

What comes next for Chile and Latin America?

As Latin America grapples with the growth of organized crime, Arica’s case offers a potential model—though not an easy one to replicate. Its success hinges on local cooperation, data-driven investigation, and international intelligence sharing.

Ignacio Castillo, director of organized crime at Chile’s public prosecutor’s office, said the Arica unit “did something that had never been done in Chile.”

Their work may not grab global headlines the way military crackdowns do, but it could prove more sustainable in the long term.

As democracy is tested across the region, and criminal networks grow more complex, Chile’s careful and coordinated approach might be the region’s best shot at disrupting the new face of organized crime.

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.