How Your Smartphone is Linked to the Deadly Conflict in the DRC

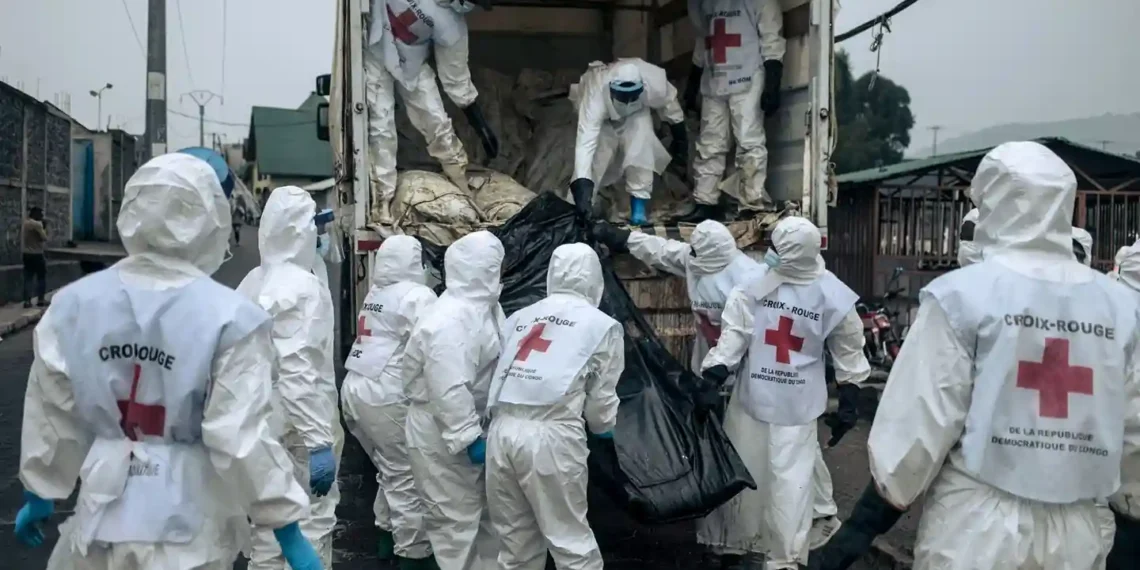

Thousands Killed as Rebels Seize Resource-Rich Areas

Fighting in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has claimed over 3,000 lives in less than two weeks, as a powerful rebel coalition, the Alliance Fleuve Congo (AFC), continues its rapid advance. The latest town to fall, Nyabibwe, is rich in coltan—a vital mineral used in making smartphones.

This comes after the AFC, with its key faction M23, took control of Goma, the largest city in the region, on January 27. The group had already seized Rubaya, another major mining hub, last year.

The Connection Between Your Phone and the Conflict

Despite its vast mineral wealth, the DRC remains one of the world’s poorest countries. Cobalt and coltan, essential for producing electronics, have become a source of conflict rather than prosperity.

- Cobalt powers batteries in smartphones and electric vehicles.

- Coltan is refined into tantalum, used in phone capacitors.

According to the World Bank, most Congolese people have not benefited from these resources. Instead, armed groups and the government compete for control, fueling violence.

“Access to natural resources is at the heart of this conflict,” says analyst Jean Pierre Okenda.

“It takes money to wage war. Access to mining sites finances the war.”

Why Do Rebels Want Control of the Mines?

The M23-led AFC has taken over the coltan-rich Rubaya and Nyabibwe mines. While the group does not openly admit to profiting from them, UN reports suggest otherwise:

- Coltan trade from Rubaya alone supplies over 15% of the world’s tantalum production.

- The UN estimates M23 earns $300,000 per month from these mines.

The DRC government and international experts accuse Rwanda of backing M23 and illegally extracting minerals.

- A UN report suggests that 3,000–4,000 Rwandan soldiers are actively supporting M23 in eastern DRC.

- At least 150 tons of coltan were allegedly smuggled into Rwanda and mixed with its domestic production.

- DRC claims Rwanda’s mineral exports have surged due to illegal mining in occupied Congolese territories.

Rwanda denies these accusations, with President Paul Kagame insisting that the country sources coltan from its own mines.

Where Do DRC’s Stolen Minerals End Up?

Last year, Kagame admitted that Rwanda acts as a transit hub for smuggled Congolese minerals, but he shifted the blame to international buyers.

“Most of it goes through here (Rwanda), but does not stay here. It goes to Dubai, Brussels, Tel Aviv, and Russia,” Kagame said, without providing evidence.

Reports suggest that:

- 90% of DRC’s gold is smuggled to Uganda and Rwanda, then exported to the UAE.

- Coltan and cobalt are harder to track, but experts believe they also enter global supply chains through regional smuggling networks.

Are Big Tech Companies Involved?

The illegal mineral trade has raised concerns about ethical sourcing among tech giants like Apple and Microsoft.

- In 2023, Apple denied claims that its suppliers finance armed groups in the DRC.

- DRC has sued Apple in Belgium and France, accusing the company of using conflict minerals.

- Apple insists it follows strict due diligence and has found no evidence linking its supply chain to armed groups.

Despite these claims, experts argue that conflict minerals still find their way into global markets due to weak enforcement.

Can This Conflict Be Stopped?

Analysts argue that DRC’s mineral wealth has become a curse rather than a blessing.

“These resources create wars, expose local populations to violence, and cause ecological destruction,” says Okenda.

A ceasefire announced by M23 last week collapsed almost immediately, as the rebels pushed further into Nyabibwe.

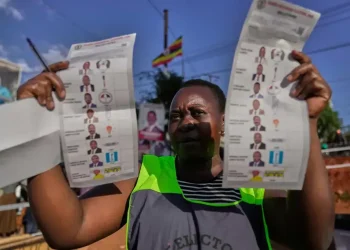

While international efforts to resolve the crisis continue, lasting peace requires governance reforms in DRC:

Stronger military investment to prevent rebel takeovers.

Fair distribution of wealth so citizens benefit from resources.

Transparent elections to ensure political stability.

Without these changes, the cycle of conflict over minerals will continue, and your smartphone may remain unknowingly linked to bloodshed in the DRC.

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.