Can Syria’s Islamist Rebels Govern the Country? Insights from Their Rule in Idlib

When Syria’s rebel-appointed prime minister met with officials from the ousted Assad regime for the first time on Tuesday, the symbolism was powerful. Behind him were two flags: one representing the Syrian revolution and another emblazoned with the Islamic declaration of faith, often associated with jihadist movements. This publicized cabinet meeting, held to discuss the transfer of power since Bashar al-Assad’s regime fell, ignited controversy. Critics on social media were quick to voice their concerns.

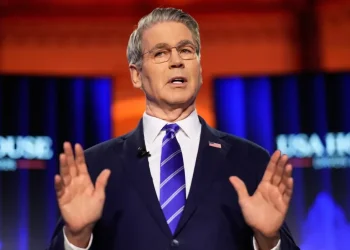

The rebels appeared to recognize the backlash. Later, in a televised interview with Al Jazeera, caretaker Prime Minister Mohammad Al Bashir—who had previously governed Idlib, a conservative province under rebel control—chose to appear with only the new Syrian flag, possibly to distance himself from earlier associations.

The Experience of Governing Idlib: A Window into the Future?

How the rebels governed Idlib offers valuable insights into their potential approach to ruling Syria. Experts and residents describe their leadership style in Idlib as pragmatic, shaped by both internal and external pressures. While they have worked to move away from a jihadist image in pursuit of international legitimacy, their rule was far from democratic or liberal. Governing a vast, diverse country like Syria, they acknowledge, will present an entirely new challenge.

Abu Mohammad al-Jolani, leader of Hayat Tahrir Al Sham (HTS)—the Islamist group that spearheaded the offensive against the Assad regime—has chosen to rule from the shadows. Jolani, now using his real name, Ahmad al-Sharaa, appointed a technocrat, Bashir, to temporarily lead Syria. Jolani reflects on the experience gained in Idlib, but he also acknowledges the limitations of their governance model.

“Idlib is small, without resources, but we managed to achieve good things. Our experience is valuable, but we must learn from the old guard as well,” Jolani told Mohammed Jalali, Assad’s prime minister, in a meeting to discuss the transition of power.

In just 13 days, Jolani’s ministers have gone from governing a small province to aspiring to lead an entire country. While they have gained some governance experience, experts warn that their capacity to lead Syria through its post-Assad era remains uncertain.

Lessons from Idlib: Strengths and Challenges

Dr. Walid Tamer, a resident of Idlib who witnessed the province’s transformation under rebel rule, praised the SSG’s governance in Idlib. He noted that freedom of expression was protected, and personal life was largely left untouched. However, he cautioned that the rebels’ experience in Idlib would not be sufficient for governing the entire country.

“You can’t just go from governing Idlib to ruling a nation,” said Tamer, the head of the Free Doctors Union in northern Syria. “The government we had in Idlib was not prepared for governing all of Syria.”

Idlib under rebel rule was “safe” and “stable,” Tamer said. There were no restrictions on movement or personal freedoms. However, economic conditions were dire. Abdel Latif Zakoor, a former resident of Idlib who now lives in Turkey, described life under the SSG as economically challenging. “There weren’t enough jobs. Many people stayed home,” he said.

The Rise of the Syrian Salvation Government (SSG)

When Jolani expanded his influence in Idlib in 2017, he eliminated rival Islamist factions and launched a new project to create a civilian government composed of technocrats and academics. This shift represented a break from other jihadist governance models, which typically relied on religious coercion.

“Before the Salvation Government, there were many factions with their own courts, prisons, and social services,” said Jerome Drevon, an expert on HTS from the International Crisis Group. “HTS imposed itself, taking over governance responsibilities.”

In 2017, the SSG issued a statement emphasizing that Islamic Sharia law would be the “sole source of legislation” and outlined the need to preserve Syria’s “Syrian and Islamic identity.” The SSG operated as a functional government, holding public cabinet meetings, issuing press statements, and managing ministries covering justice, education, and sports. It also collected taxes and coordinated with humanitarian organizations to aid the region’s 3 million displaced people.

However, the SSG was not a democratically elected body. Ministers were appointed through the approval of a shura (consultative council), many of whose members were selected by HTS. Notably, no women held leadership positions during the SSG’s seven years in power.

An Islamic, Technocratic Approach

Drevon described the SSG’s governance as a blend of Islamic rule and technocratic management. “They wanted to control how religion was understood and implemented,” he said.

Yet, the SSG’s rule was not without its flaws. A 2022 United Nations report painted a grim picture of life under HTS, highlighting concerns about human rights violations, lack of political freedoms, and harsh restrictions on freedom of expression.

The Road Ahead

The transition from ruling a small province like Idlib to governing all of Syria presents a daunting challenge for the rebels. While their experience in Idlib has equipped them with valuable lessons in governance, it remains to be seen whether they can adapt to lead a nation that has been ravaged by over a decade of civil war. Their ability to balance their ideological goals with the practicalities of governance will likely be key to their success—or failure—on the national stage.

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.