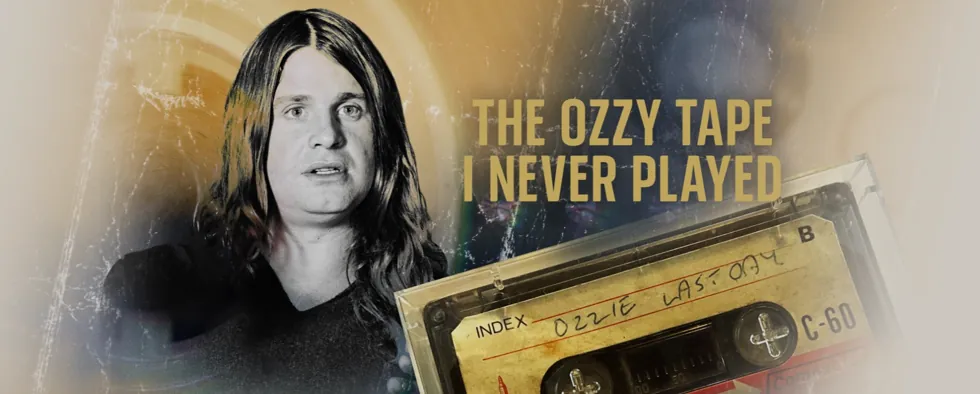

In a small Suffolk studio, a faded cassette labelled “Ozzie Last Day” played for the first time in decades, offering an unexpected window into a turning point in Ozzy Osbourne’s life. The recording is not a lost album or a forgotten demo. Instead, it preserves fragments of a rehearsal jam from January 1980, when Osbourne was rebuilding his career after being dismissed from Black Sabbath.

What survives on the tape is modest in length but rich in meaning: faint vocals, a clear guitar line, and the unmistakable chemistry between Osbourne and the young guitarist Randy Rhoads. Together with bassist Bob Daisley and, at that point, before a permanent drummer was secured, the musicians were shaping the sound that would soon emerge as Blizzard of Ozz.

For music historians and fans, the tape offers something rarely captured — the sound of a band in formation, at a moment when success was far from certain.

The make-or-break winter before Blizzard of Ozz

By mid-1979, Osbourne described himself as “unemployed and unemployable.” After 11 years fronting Black Sabbath, the band he helped found in Birmingham, he had been fired and retreated to Los Angeles in a haze of uncertainty.

A management offer from Sharon Arden, who would later become his wife, prompted a slow return to work. Through auditions, Osbourne met Rhoads, a 22-year-old classically trained guitarist from California, and Daisley, an experienced Australian bassist. After numerous attempts to find the right drummer, the group’s final line-up would eventually include Lee Kerslake of Uriah Heep.

Much of the recording history of Blizzard of Ozz — made later in 1980 at Rockfield Studios in Wales and Ridge Farm in Surrey — is well documented. Far less known are the early January rehearsals in rural Suffolk, where the musicians lived and played together while refining their ideas.

It is from this period that the cassette originates.

A tape kept in an attic for 45 years

The tape belonged to David “Chabby” Jolly, who worked in the area at the time and struck up an informal friendship with Osbourne during the rehearsals in Ilketshall. According to Jolly, Osbourne handed him the cassette on the final day before leaving.

He stored it in a briefcase in his attic and largely forgot about it. After hearing of Osbourne’s death decades later, he searched for the tape and decided to have it professionally played for fear that the ageing cassette might be damaged.

At first, the playback seemed disappointing. The unmistakable organ introduction to Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Free Bird suggested the original recording might have been taped over. But after a pause, a guitar line emerged, followed by faint vocals that were immediately recognisable.

“That’s Ozzy,” someone in the room said.

The roughly 60-minute cassette contains about 12 minutes of rehearsal audio — blues-leaning improvisations rather than structured songs. Rhoads’ guitar is clear; Osbourne’s voice is present but distant. The musicians can be heard jamming, muttering between passages, and working through ideas.

No complete song can be identified, but the tone recalls Osbourne’s early blues influences before Black Sabbath’s heavier direction took hold.

Bob Daisley recognises the moment

Bob Daisley, now living in Australia and the only surviving member of that early line-up, listened to the recording by phone.

“As soon as I heard it, I thought, yes, that’s us, that’s Ozzy’s voice,” he said. He believes the tape predates the arrival of Kerslake, placing it early in the rehearsal period when the group was still experimenting.

“We had definite songs by then,” Daisley said, “so this wasn’t something we were working on for the album. It sounds like we were just loosening up.”

Daisley kept diaries and rehearsal recordings from his career but said he had nothing like this particular session. He remembers the farmhouse where they stayed, with its low wooden beams, and recalls taking early versions of their songs to a local pub to test audience reaction.

“When we played what we had written, it felt good,” he said. “We thought, yes, this is working.”

Nine months later, Blizzard of Ozz would be released, featuring Crazy Train, Mr Crowley and Suicide Solution — songs that re-established Osbourne as a solo artist and reshaped heavy metal in the early 1980s.

More artefact than lost music

Music historians say the tape’s value lies less in the audio quality and more in what it represents.

Jez Collins of the Birmingham Music Archive described it as “an incredible artefact”.

“It’s not a lost master tape that’s going to be sold for millions,” he said. “But it captures a really significant moment — the point where Ozzy is finding his way again after Black Sabbath.”

Collins also noted the rarity of hearing Osbourne and Rhoads at such an early stage of their partnership. Rhoads died in a plane crash in 1982 at the age of 25, having recorded only two studio albums with Osbourne.

“To hear them in a room together like this is unusual,” Collins said. “You don’t often hear the beginnings of a musical relationship because those tapes are usually wiped or lost.”

Anthony Crutch of Birmingham Museums Trust, which has hosted exhibitions on Osbourne’s life, said the tape reflects a period when Osbourne was largely out of public view.

“Nobody knew at the time if a solo career would work,” he said. “There probably weren’t high expectations.”

Crutch believes he can hear Osbourne vocalising what sounds like the intro to Sabbra Cadabra, a Black Sabbath track from 1973, suggesting that even during this transitional phase, Osbourne’s past and future were intertwined.

A brief friendship and lasting memory

For Jolly, the tape is personal before it is historical.

He remembers Osbourne as humorous and unassuming, far removed from his public persona. He recalls trips to local pubs and moments of slapstick humour, including Osbourne mistakenly washing himself with carpet shampoo.

“When you’re that age, you don’t think you’re witnessing history,” Jolly said. “I just saw him as a friend.”

The rediscovered cassette now stands as a small but vivid record of the weeks when Osbourne’s career was being rebuilt from uncertainty. It does not contain a hit song or a forgotten demo. Instead, it preserves the sound of musicians finding their footing — the early stirrings of a comeback that would soon reach millions.

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.