More than five centuries after Leonardo da Vinci’s death, scientists searching for biological clues to his extraordinary abilities are turning to an unconventional source: the objects he once touched. With no confirmed remains to analyse, researchers are now examining artworks and documents linked to the Renaissance master for traces of genetic material.

Early findings suggest it may be possible to recover fragments of human DNA from centuries-old paper and drawings without damaging them. While researchers stress that none of the material identified so far can be definitively linked to Leonardo himself, they say the work lays the groundwork for future genetic investigation into one of history’s most studied figures.

The research forms part of the Leonardo da Vinci Project, an international effort that combines genetics, art history and conservation science. Results released this month describe what the team calls a proof of concept rather than a breakthrough — but one that could reshape how historical figures are studied when human remains are unavailable.

A problem centuries in the making

Leonardo, who died in France in 1519, left no known children. His burial site at the Chapel of St. Florentin in Amboise was destroyed during the French Revolution, and bones later recovered from the ruins have never been conclusively authenticated.

In the absence of verified remains, project researchers explored whether DNA shed through touch might still be detectable on objects Leonardo handled. Paper, canvas and drawings can absorb biological material such as skin cells, sweat and oils, which may persist for centuries under the right conditions.

Leonardo’s surviving body of work — including letters, notebooks and drawings — offers rare opportunities for this type of analysis. The challenge, scientists say, is extracting genetic material without harming irreplaceable cultural artifacts.

Testing a minimally invasive method

To address that concern, the research team first evaluated several sampling techniques commonly used in forensic science, including punch sampling, vacuuming and wet swabs. After extensive testing, they concluded that dry swabbing could recover sufficient DNA while posing minimal risk to the objects.

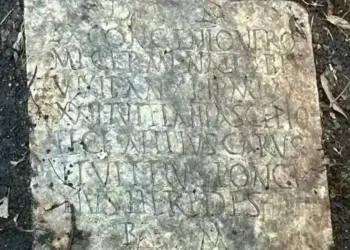

The team applied the method to several items, including letters written by a distant relative of Leonardo and a drawing known as Holy Child, which some experts attribute to Leonardo, though the attribution remains disputed.

The samples yielded large amounts of environmental DNA — genetic material from bacteria, plants, fungi and animals that accumulated over hundreds of years. Among those traces, researchers also identified fragments of human Y chromosome DNA from both a letter and the drawing.

The findings were published on January 6 as a preprint and have not yet undergone peer review.

“There’s a lot of biological material that comes from the individual that can be tracked to a piece of paper or a canvas,” said Dr. Norberto Gonzalez-Juarbe, a study coauthor and assistant professor at the University of Maryland. Layers of paint, he noted, can even help preserve material by shielding it from environmental exposure.

Clues from environment and history

Beyond human DNA, the environmental genetic profile offered insights into where and how the artwork may have been produced and stored.

After filtering out likely contaminants such as modern dust, the researchers identified plant and animal markers consistent with Renaissance Italy. DNA from citrus trees was detected on the Holy Child drawing, which the team believes could be linked to Tuscany, where the Medici family cultivated rare citrus varieties.

Wild boar DNA was also found. Art historians note that stiff bristles from wild boar were commonly used in Renaissance paintbrushes, making the finding consistent with known artistic practices of the period.

“Are we completely certain where that animal DNA comes from? No,” said Dr. Charles Lee of The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine, another coauthor. “But it aligns with what we know from art history.”

A tentative genetic signal

Lee’s team focused on the human component of the samples. Working under blinded conditions, they analysed Y chromosome fragments from multiple swabs and compared them with extensive reference data used in population genetics.

They found that Y chromosome markers from one letter and the Holy Child drawing were genetically related and belonged to the E1b1 haplogroup — a paternal lineage found today in parts of Italy and more broadly across Europe and North Africa.

In modern Tuscany, E1b1 is estimated to occur in a minority of males, though it is not rare. Geneticists believe the lineage entered Europe thousands of years ago through migration from North Africa.

The geographic signal is consistent with Leonardo’s birthplace and life in Italy. However, researchers emphasise that the presence of this haplogroup does not establish authorship of the drawing or prove the DNA belonged to Leonardo.

“This is not definitive proof,” Lee said. “It’s an initial observation and a foundation for collecting more data.”

Skepticism and scholarly caution

Some art historians and forensic experts urge restraint. Francesca Fiorani, a professor of art history at the University of Virginia who was not involved in the study, questioned the choice of materials used for analysis.

The attribution of Holy Child to Leonardo is not widely accepted, she noted, and a document written by Leonardo’s father — a closer genetic relative — would likely be more informative if available.

“DNA research can add valuable insights,” Fiorani said, “but in Leonardo’s case there is no secure way to access his DNA because no authenticated remains exist.”

Others, however, see promise in the approach. S. Blair Hedges, a biologist at Temple University, described the methodology as impressive and said it could eventually contribute to building a genetic profile if multiple independent lines of evidence converge.

What comes next

Researchers involved in the Leonardo da Vinci Project say further work is already underway. Efforts include sampling lesser-handled notebooks and drawings held in French collections, analysing material from living descendants of Leonardo’s father, and re-examining disputed bone fragments believed by some to be Leonardo’s.

Consistency will be key. If the same Y chromosome lineage appears across authenticated artifacts and related family lines, scientists say confidence would increase.

Even then, reconstructing a full genome — and linking it to traits such as visual acuity, which some researchers speculate may have contributed to Leonardo’s abilities — remains a distant goal.

For now, the study underscores both the possibilities and limits of applying modern genetics to historical figures.

“We don’t know where this journey will end,” Lee said. “And that uncertainty is part of what makes the work worthwhile.”

This article was rewritten by JournosNews.com based on verified reporting from trusted sources. The content has been independently reviewed, fact-checked, and edited for accuracy, neutrality, tone, and global readability in accordance with Google News and AdSense standards.

All opinions, quotes, or statements from contributors, experts, or sourced organizations do not necessarily reflect the views of JournosNews.com. JournosNews.com maintains full editorial independence from any external funders, sponsors, or organizations.

Stay informed with JournosNews.com — your trusted source for verified global reporting and in-depth analysis. Follow us on Google News, BlueSky, and X for real-time updates.